Chapter 14

After the “War Economy”

By John Dowdy and Andrew Erdmann

The challenge in Afghanistan is how to build, strengthen and sustain a state that can provide security, stability and support to its people in the face of resilient insurgencies. This chapter argues that the international community’s approach to addressing this state-building challenge – especially during the period of transition as most international security forces withdraw from Afghanistan by the end of 2014 – needs to recognise more fully the strategic importance of private sector economic development in three areas:

- The creation of a sustainable public finance model for the Afghan state so that the government can perform its essential functions without being a permanent ward of the international community. Where is the money to come from except through private sector development of trade, industry, and, most important, natural resources?

- The integration of Afghanistan both internally and with its neighbours. Business ties can help create, nurture and solidify interests and networks across fault lines within a fragmented Afghanistan, and between it and its neighbours, as well as the international community beyond.

- The provision of livelihoods for the populace – including former insurgents attempting to reintegrate into society – leading to a rising standard of living.

However, since 2001, despite numerous policy pronouncements that only an integrated political-military-economic strategy – a “whole of government” solution – can succeed in Afghanistan, the so-called “economic line of operations” has taken a back seat to the security and governance challenges that dominate the agenda of government and international meetings.86

Even within the “economic line of operations”, other economic activities have eclipsed private sector development. In the offices of the defence and foreign ministries around the world, international financial institutions, international organisations, and in Kabul, the lion’s share of attention among those working on Afghan economic policy is devoted to what might be called “macro-policy” issues. These include maintaining the overall architecture of assistance under the International Compact with Afghanistan; reviews of Afghan macro-economic health, including inflation, currency stability and debt relief; and policy reform and capacity building in ministries in Kabul.

In the field, much of the remaining development investments have focused upon large-scale infrastructure projects and grassroots development work aimed at tackling basic human needs encapsulated in the UN Millennium Development Goals. Although intended to be focused on tactical counterinsurgency (COIN) objectives, the US military’s Commander’s Emergency Response Programme (CERP) funds have likewise emphasised basic infrastructure, with over 60 percent committed to transportation-related projects between 2005 and 2009.87

These development investments have merit and are worth evaluating on their own terms.88 Many have indirectly promoted private sector development, such as when a new road reduces the time to market for perishable crops. However, direct support for private sector development has represented only a sliver of overall assistance to Afghanistan. As such, it does not seem overly provocative to suggest that private sector development has been “doubly missing” from the international community’s Afghanistan strategy to date.

The peculiar implications of this neglect of the Afghan private sector can be seen first-hand on many military bases around Afghanistan. Consider this example. In late 2009, the United States and the United Nations together launched the “Afghan First” procurement policy to channel contract spending to competitive local businesses.89 Yet only a small fraction of the roughly $14 billion the Department of Defence procured at that time went to Afghan firms. In September 2010, General David Petraeus issued guidance to all NATO and US military personnel serving in Afghanistan that emphasised the strategic importance of directing international contracting spend to both promote economic development and to avoid strengthening actors that undermine Afghan security.90 A decade after the international intervention in Afghanistan began, palettes of bottled water can still be found imported from the UAE on a US base that is within a few miles of at least three separate Afghan water bottling plants, whose owners would welcome contracts with international forces.

Why should this be so? It may simply be that people and organisations naturally gravitate to issues and solutions with which they are familiar, and where they feel they have answers. By and large, Western policymakers, by training and experience, are more comfortable with providing security, political and diplomatic solutions rather than facing the challenges of small and medium enterprise (SME) development, business plans and attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). Likewise, our development agencies, contractors and NGOs are more comfortable with technical assistance, infrastructure projects (with more easily quantifiable outputs to measure progress) and grassroots development initiatives. Deep private sector – let alone entrepreneurial – experience is often in short supply in such organisations. Contracting organisations and officers traditionally focus upon reliability in cost and delivery of goods and services in making their decisions, not on potential implications for local economic development and stability. And most Afghans still have difficulty navigating through procurement processes that are of byzantine complexity.

This chapter sets the context with a brief discussion of Afghanistan’s economic inheritance and the economic challenges involved in the current transition in the international community’s presence in Afghanistan; it suggests at a high level what is involved in meeting these challenges, argues for the necessity of an approach that explicitly prioritises investments in certain sectors and industries, and closes with the implications for the international community’s Afghanistan strategy, policy and execution.91

AFGHANISTAN’S ECONOMIC INHERITANCE

At first blush, Afghanistan appears to present a hopeless development challenge. Afghanistan is a desperately poor place, ranking at or near the bottom on every global measure of economic and human development.92

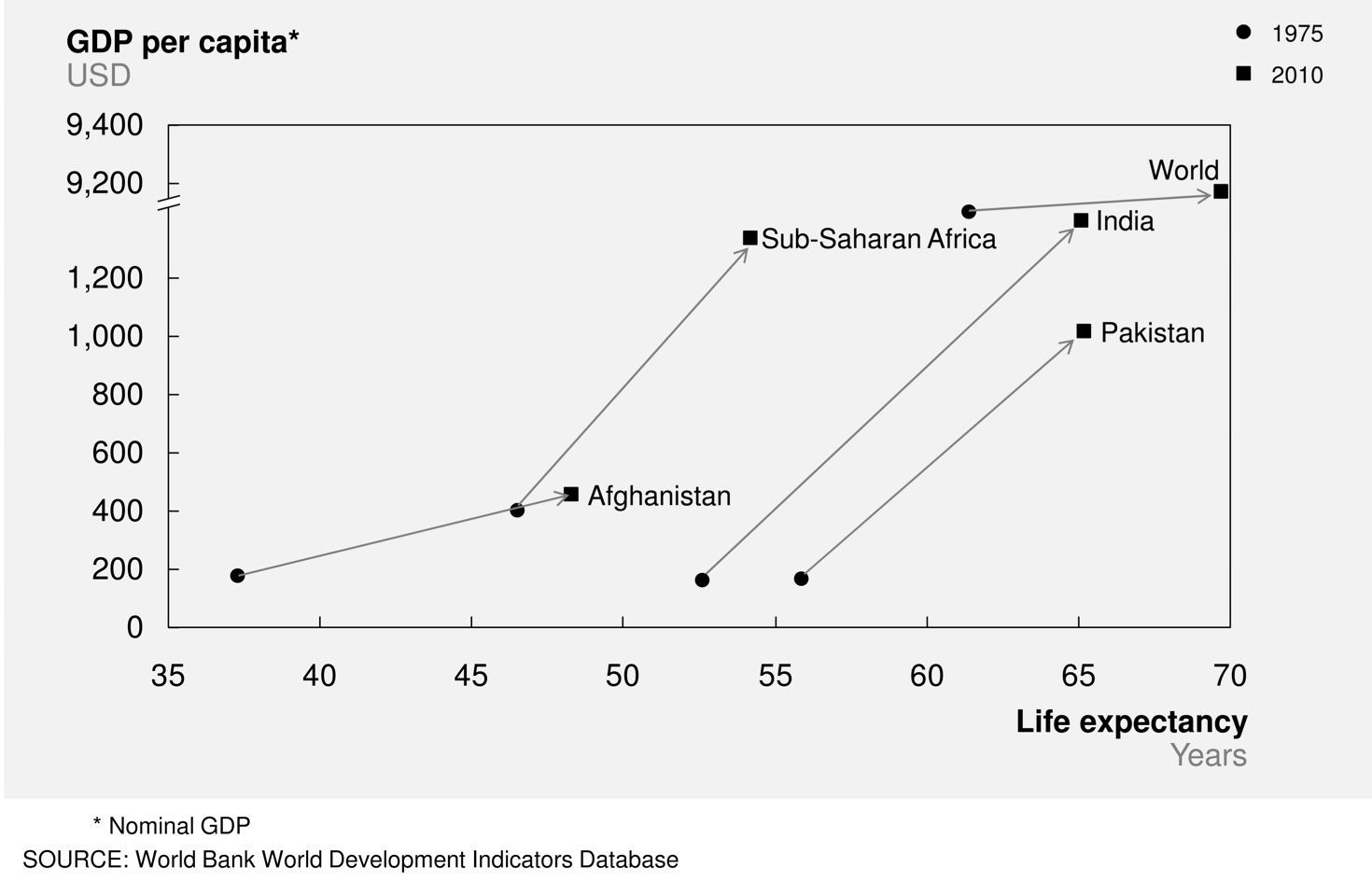

EXHIBIT 1: Afghanistan has lagged its neighbours and the rest of the world in economic and human development during the last 30 years

In 1975, Afghanistan’s per capita income was slightly higher than India and Pakistan. In the following 35 years, both countries – and even Sub- Saharan Africa – left Afghanistan behind (Exhibit 1).93 If Afghanistan has been distinctive at one thing since the mid–1970s, it has been in exemplifying the “traps” – to adopt Paul Collier’s terminology – that retard development in “bottom billion” countries.

First, and most importantly, Afghanistan has been caught in a “conflict trap”: the Soviet invasion in 1979; the long, savage war waged by the Soviets and their Afghan allies against the mujahedin; the Afghan civil war following the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 that eventually propelled the Taliban’s rise to power; the Taliban–Northern Alliance war; the US-led overthrow of the Taliban regime; and the current war against the Taliban insurgencies.

Second, Afghanistan is landlocked and surrounded by “bad neighbours”, in Collier’s parlance.

Third, Afghanistan suffers from “shaky” governance.

Fourth, even its recently trumpeted wealth in natural resources poses a potential “resource trap” to Afghanistan’s development and governance, as a look at the experience of Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo or some other resource-rich countries would suggest.94

All this has resulted in profound structural challenges to Afghanistan’s development. The overall effect of these challenges, especially the “conflict trap”, has been to shrink the economy from $3.7 billion annual GDP (nominal) in 1979 to less than $2.5 billion in 2001, destroy infrastructure, livestock and crops, scatter a diaspora of educated Afghans around the world, stymie the once-profitable natural gas industry, deter most outside investors, and foster the explosion of an illicit poppy economy.95

The Afghan experience before the political instability of the late 1970s, however, shows that development has been possible. During the reign of King Zahir Shah (1933–73), trade expanded around 8 percent per year.96 Formal education grew from a mere 1,350 students in 1932 to over 830,000 in 1974.97 The economy grew modestly but steadily at about 3 percent per year between 1960 and 1973.98

Afghanistan also initially benefitted from Cold War competition as both the United States and the Soviet Union poured development assistance into the country in the late 1950s and 1960s. Helmand Province was known then as “little America” because of the extensive US development presence. Above all, basic infrastructure – especially the national road network – expanded, thereby linking Afghanistan’s regions together as never before.99 In many respects, therefore, the 1979–2001 period represents not the normal path, but a disastrous detour on Afghanistan’s road to development.

There are signs since 2001 that Afghanistan has been getting back on track. Like many post-conflict economies, Afghanistan has experienced roughly 10 percent annual GDP growth on average during the past decade – albeit with significant volatility tied to weather, agricultural production, commodity prices and the security environment.100 The economy rebounded well from the global downturn: Afghan GDP grew 21 percent in 2009 and 8.4 percent in 2010. 101Afghanistan has a good record on currency stability and inflation. Exports increased more than five-fold between 2002 and 2008 – but they have since dipped, and in 2011 stood at only 69 percent of their 2008 peak.102 Vehicles on the road grew from just over 175,000 to nearly one million between 2003 and 2009, helping to accelerate the movement of people and goods despite the woeful state of basic infrastructure in most areas. SME production has expanded to supply the growing local market and has started to displace the imports that dominate nearly every category of good. Between 2002 and 2009, for example, annual production of shoes and plastic sandals increased 75 percent per year, from one million to over 28 million pairs, and plastic dishes increased 45 percent per year, from 11,000 tons to 98,000 tons.103 An industrial park built outside Herat, for example, boasts over 160 companies and 25,000 employees working in food and beverage processing, marble cutting, plastics, iron, and other profitable industrial businesses. The explosion in cell phone usage – from close to nothing in 2001 to now over 18 million cell phone accounts in a country of roughly 35 million people – is perhaps the most visible example of how the opening of the Afghan economy is changing lives in new ways.104 The World Bank estimates, moreover, that internet users will more than double between 2011 and 2013, from one million to 2.4 million users.105 In parallel with these economic developments, Afghanistan has made significant progress in the past decade on a variety of measures of social development such as life expectancy and education – in large part due to international development assistance since 2001.

Beyond a recitation of statistics, it is important to note Afghanistan’s long history and deep culture as a trading nation, a fact vital to explaining this recent success, and which offers some hope for the future. This represents the living legacy of the Silk Road. Equally important – and in contrast to other countries such as Iraq – the Afghan state never asserted control over the entire economic sphere. Major industries were state-owned according to the 1977 constitution, but even the move to extend state control under the Afghan communists was halting and incomplete. Overall, state-owned enterprises represent a small and shrinking portion of the Afghan economy. If you speak to Afghan SME owners and entrepreneurs, you would be impressed by their dynamism, determination and business acumen. They can cite cost differentials in supply chain options down to the Afghani, how Turkish, Iranian, Indian and Chinese equipment compares, what they need and how they will train their staff. Although they typically lack formal business training and refined technical and communication skills, Afghan businessmen know how to think through business problems by a combination of experience, intuition and tradition.

Today, Afghanistan and its economy still confront profound challenges – challenges exacerbated by the transition in international security and development assistance linked to the winding down of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission by the end of 2014. Business uncertainty has increased hand-in-hand with political and security uncertainty. Some indicators suggest new business start-ups have slowed. Falling global prices for commodities such as copper have reduced the attractiveness of some of Afghanistan’s natural resources, at least in the near term. As Afghanistan is moved off the front pages and donors scale back their presence in country, some of the most skilled and experienced international experts have moved on to other countries. The World Bank has projected that Afghanistan’s annual GDP growth rate will likely fall 3 to 4 percent and unemployment increase in the coming years as international spending and assistance are scaled back.106

However, the impact on Afghanistan of the international presence and assistance during the past decade has been mixed. As the World Bank argues, “aid has underpinned much of the progress since 2001 – including that in key services, infrastructure, and government administration – but it has also been linked to corruption, fragmented and parallel delivery systems, poor aid effectiveness, and weakened governance.107” Furthermore, the economic effects of the drawdown of international security forces and reduction of foreign aid will likely be not as severe as one might think. Why? Because in practice only a minority of the aid for Afghanistan – estimated to be less than 40 percent – “actually reaches the economy through direct salary payments, household transfers, or purchase of local goods and services”.108 To be sure, the drawdown in international presence in Afghanistan will likely have negative implications for the Afghan economy. That said, it will also give Afghanistan and its neighbours the opportunity to foster more “natural” and sustainable economic relationships, with a reduced dependence upon international donors.

MEETING THE CHALLENGES

It is in this context that the challenges of building a sustainable public finance model for the Afghan state, integrating Afghanistan internally and with its neighbours, and providing livelihoods for the populace must be understood.

Public finance

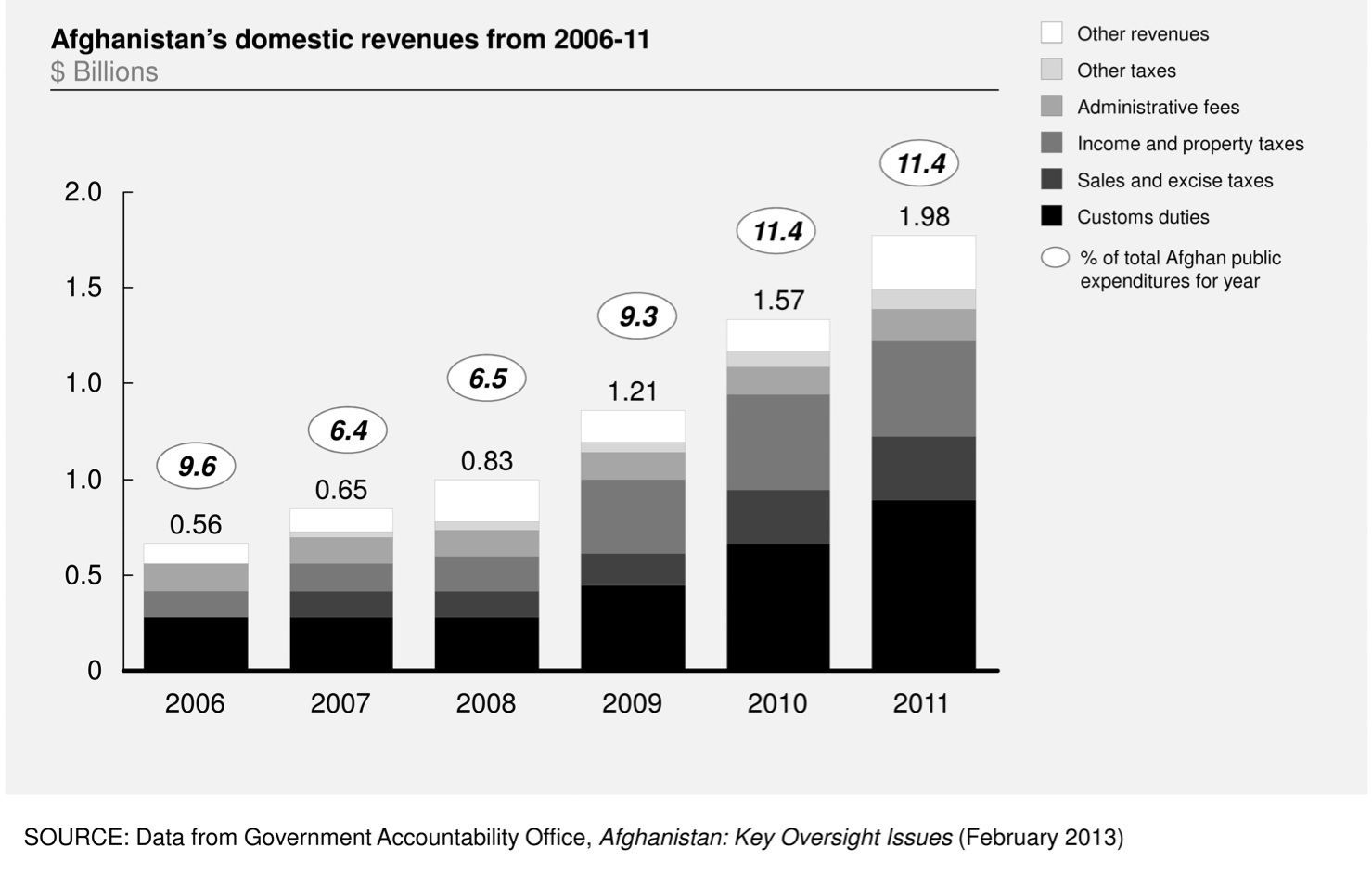

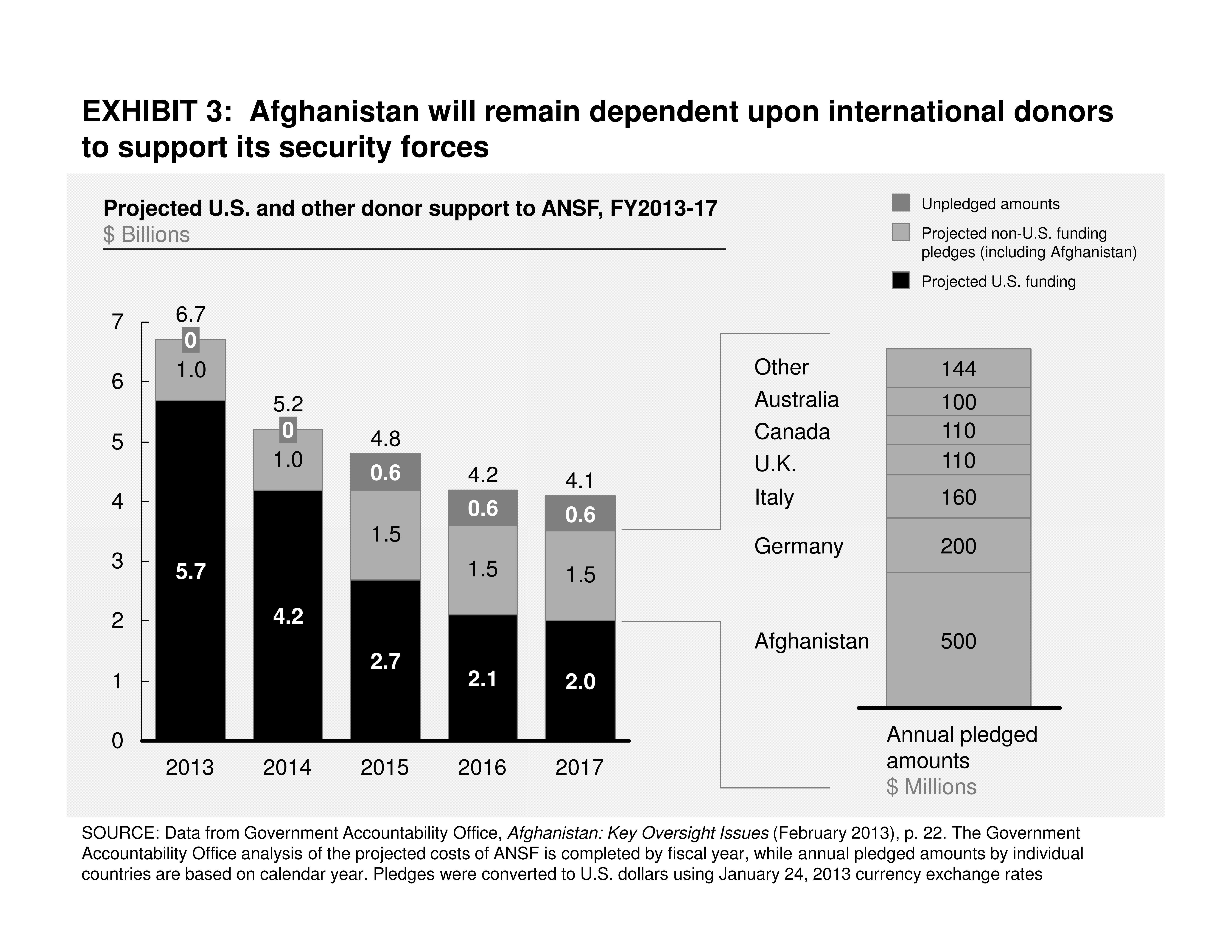

Afghanistan remains a ward of the international donor community. Funding requirements for security – to build and sustain the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), comprised of the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police – far surpass today’s indigenous public revenues (Exhibits 2 and 3). The public finance gap is expected to “increase sharply” in the coming years.109 Even if the Afghan government committed all its domestic revenues, it still would not be able to fund all the ANSF’s requirements. This situation will likely not change in this decade.110 When Afghan and international donor community leaders convened at the Chicago Summit in May 2012, they set the goal for Afghanistan to “assume, no later than 2024, full financial responsibility for its own security forces”.111 This profound imbalance and dependency upon international donor assistance poses a challenge to Afghanistan’s “economic sovereignty” and thereby the viability of the Afghan state-building endeavour.112

Duties on trade and other tax revenues are important, but insufficient to close the public finance gap. The long-term answer, therefore, lies in the responsible development of Afghanistan’s vast natural resources, especially minerals and energy. Today, mining accounts for only a sliver of Afghan GDP, but has significant potential113. Afghan officials have stated that they believe the country’s reserves of natural resources might well be worth over $3 trillion dollars in the coming decades – or over $100,000 per Afghan citizen, in a country with an annual per capita GDP today of around $500.114 In 2012 the US Geological Survey completed an aerial survey of Afghanistan’s potential mineral deposits, though the ultimate value of the deposits will not be known for years115. Taxes, duties and royalties from the development of these resources could eventually provide hundreds of millions or billions of dollars every year to the Afghan treasury.

EXHIBIT 2: Afghanistan's domestic revenues have grown steadily since 2006 but have not bridged the massive public finance gap

Natural resources are the only “game changer” available. Local Afghan firms are already mining industrial materials such as marble, gravel and sand. Yet only globally traded minerals such as copper, iron, gold and rare earth elements and energy supplies have the potential to generate significant public revenues. This will necessarily involve major international mining and energy companies, since the Afghans do not possess the indigenous capabilities themselves. The development of the Aynak copper reserves demonstrates that the Chinese are willing to enter the Afghan market, and a consortium of Indian companies was awarded a $10 billion deal to begin iron ore mining operations in the Hajigak region.116 Production of oil in Amu Darya and gas in Sherbeghan are again beginning to show promise. Recognising the central importance of these developments, the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan has launched its National and Regional Resource Corridors Programme (NRRCP) with the support of international partners such as the World Bank. The NRRCP aims to harness investments in extractive industries to generate broader economic gain for the country.117 Facilitating additional international private sector engagement in this area is therefore critical – while also helping the Afghans put in place safeguards against a “resource curse”.118

Addressing the public finance gap will also hinge upon basic functioning of the Afghan state. Corruption at all levels of the Afghan state threatens the foundations of public finance, as well as the legitimacy of the government in Kabul. Polling of Afghan citizens highlights the pervasiveness of corruption and less than a third feel that the national government is doing a good job in fighting corruption.119 In 2012, for instance, customs collections fell almost 10 percent despite the fact they had been steadily climbing during the past decade and overall imports continue to rise. Customs revenues account for approximately one-quarter of total public revenues. The silver lining to this particular cloud is that the Ministry of Finance took action and replaced the leadership and staff overseeing customs.120 Looking to the future, targeted capability building will still be required to help the Afghan state deliver a baseline of services related to public finance, competently and professionally.

Integrating Afghanistan

Business and trade relations can help build networks of shared interests that transcend traditional territorial and ethnic boundaries. Today, Afghanistan is fragmented economically, as well as politically. Afghan businessmen look outward to their more-developed and easily accessible international neighbours as much as, if not more than, they look within their own country. Speaking with businessmen in the different regions of Afghanistan throws this reality into stark relief. In Jalalabad, business ties and supply chains flow into Pakistan. In Mazar-e Sharif, you see imported goods from Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and hear talk of how the country’s first railway line now links Mazar-e Sharif to the Uzbek rail network, and then to the European network, thus further accelerating trade relations. In Herat, electricity flows from Iran, along with hundreds of trucks carrying goods overland every day via the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas. Although plagued by delays, Herat may soon be linked to the Iranian rail network. Such business ties across international borders are inevitable and largely beneficial. Afghanistan’s development should be accelerated by connections to international markets. However, they can be unhealthy if they reinforce centrifugal forces within Afghanistan. Afghanistan’s internal market still has limited interconnectedness and this poses potential long-term negative implications for the viability of the Afghan state.121

It is crucial to encourage and support wherever possible the development of deeper private sector relationships across regions inside Afghanistan. SMEs involved in light manufacturing, trade, construction and logistics are potential leaders for such integration. Doing this will reinforce the broader strategic goal of integrating Afghanistan. This would also work in tandem with the natural tendency for Afghan businessmen to seek to integrate vertically their own “value chains” by expanding into transportation and distribution in order to reduce the risks and transaction costs in a society with inconsistent rule of law.

Continued infrastructure investment, alongside improved security, should help Afghanistan restore the internal market links that have been torn apart in the past three decades, as well as develop strategic trade corridors linking north with south, and east with west, to rejuvenate regional trade across a “New Silk Road”. The United States has heralded the “New Silk Road” initiative as critical to Afghanistan’s successful transition.122 To date, progress has been modest among neighbours, with their different interests and ambitions in the region. Progress often depends upon basic administrative improvements – such as developing and implementing more streamlined processes to expedite legitimate commerce between Afghanistan and its neighbours.

In sum, it will be much harder to achieve a sustainable political settlement without some kind of mutual reinforcement of internal and regional economic interests.

Providing livelihoods

What the average Afghan citizen cares most about is: “How will I and my family survive?” The first concern is security – but that security is economic as much as, or perhaps even more than, it is physical.123 A basic standard of living is essential. Outside direct government employment – especially in the security forces – these livelihoods come from the private sector. Moreover, roughly two-thirds of Afghan workers in the agricultural sector are in some way connected to the private sector, and their fates are intertwined. Positive, visible private sector growth will be seen as an indicator of state effectiveness.

But there is a more immediate need for private sector job creation, as a way of helping counter the appeal of the Taliban and other “spoilers”. Baldly put, when the Taliban’s representative arrives and says he can give a job, and if the government has been saying for months that it can too but hasn’t done so, then the Taliban representative will win. Moreover, jobs are an important element in the disarmament–demobilisation–reintegration (DDR) programme that could bring many Taliban “in from the cold”.124 Providing jobs and demonstrating that the Afghan state can deliver on its commitments to its people is where economics connects most directly with the strategic goals of reconciliation and stabilisation. As in Iraq, a large part of the success of “the surge” was the fact that, when dealing with the Sunni insurgency, the United States put a lot of people on the payroll. It was, in effect, a huge temporary public works programme. But such programmes need to transition to a sustainable private sector basis to endure. The adage remains true: idle hands do the devil’s work.

A PRIORITY SECTOR AND INDUSTRY APPROACH

How can private sector development accelerate to secure these strategic goals? Philosophically, it is important to recognise that there are different models for private sector development, with different balances between the state, firms and individuals, depending upon the unique history, culture, natural endowments and structure of economies. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.125 In countries such as Afghanistan, a reflexive “pure free market” approach is not viable.

What is necessary in any model is a sector competitiveness analysis that guides the use of limited resources according to their highest strategic impact. This should not be framed in terms of “picking individual winners,” but rather of identifying the industries with the highest potential, and then tailoring policies and other support to accelerate the development of these industries.126

To date, most approaches to private sector development have emphasised those goods where Afghanistan has potential long-term competitiveness in the international marketplace. These include marble, fruits, nuts and other agricultural products (including niche ones, such as saffron), handicrafts (especially carpets), and minerals and energy. Prioritising these industries make sense. Exports bring in much-needed foreign currency, and Afghan development should focus upon industries where there is the promise of sustainable competitive advantage. But export-oriented opportunities represent, at most, half the story.

Agriculture deserves a chapter of its own. It represents approximately 60 percent of employment and a quarter of GDP.127 These numbers will decrease in time as the economy matures. For now, however, agriculture must be a priority, or any economic development strategy would ignore the vast majority of the population. The agricultural sector is typically a leading driver of long-term growth in developing economies.128

Another part of the story is the non-tradable industries, especially in the services and infrastructure sectors. Non-tradable industries in these sectors (such as trade, retail, construction and transportation) typically account for half of GDP and approximately two-thirds of employment growth in developing economies.129 Since 2001, they have been major drivers of growth.130 Construction services and materials have great potential in Afghanistan, driven by significant local and donor demand, and because they support the development of all other industries.

Rounding out the story is the whole panoply of light industry – stuff ranging from food processing to paints and plastics. Although technically tradable, these are not an “export play”, but viable businesses that can substitute for the imports that currently feed local Afghan demand. Despite higher costs on some inputs, such as electricity, local Afghan firms can often be cost-competitive because they have much lower transport costs as well as lower labour costs.

These sectors and industries can be mapped back to our three strategic priorities. Tapping Afghanistan’s natural resource wealth will provide the largest part of public finance. Transit, trade and SMEs will help integrate the Afghan market locally, regionally and internationally, and provide new jobs. And improving agricultural productivity and yields will help the majority of the population move up from borderline subsistence.

Sustained execution of such a strategy is more challenging than devising it. Security remains an obvious concern. Enormous infrastructure challenges remain. Electricity supply, for instance, is often unreliable and expensive, thereby weakening Afghan goods’ competitiveness. Afghanistan is one of the worst places in the world for the “ease of doing business”, with its stultifying corruption and often capricious bureaucratic processes. And perhaps the biggest constraint on SME growth, as reported in interviews with SME owners around the country, remains the lack of access to credit.131 The crisis in the Kabul Bank that unravelled in September 2010 exemplifies the general weakness of the Afghan financial system.132 Recent interviews confirm that the chronic lack of available credit continues to plague the Afghan economy nearly three years after the Kabul Bank debacle.

Despite these challenges, the potential upside is significant and realistic. While not minimising the security challenges, one can see “business as usual” moving forward wherever the environment reaches a baseline of stability. Modest improvements in performance can deliver step changes in value added, precisely because of the primitive condition of much of the Afghan economy. The marble industry illustrates this pattern along its entire value chain, from extraction to polishing. The use of primitive extraction and cutting techniques (including blasting with unexploded ordnance) can destroy up to 80 percent of the value of Afghanistan’s world-class marble. Widespread introduction of improved techniques, which have been successfully piloted, would eliminate this wastage. Furthermore, much of the final value-added processing – refined cutting and polishing, worth perhaps 10 percent of the marble’s ultimate value – is often completed in Iran or Pakistan. As one marble factory owner lamented: “We do the hard job and they get all the benefit.” Similar patterns can be seen in agriculture, the carpet industry and other industries as well.

Put another way, there is real worth in Afghan work, but much of it is lost and then the remaining value captured by others. This cycle epitomises both the tragedy and potential of the Afghan private sector.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY’S ECONOMIC STRATEGY, POLICY AND EXECUTION

What is to be done?

First, private sector development must be given the priority it merits. It holds the key to a sustainable model of public finance and encourages networks, interests and shared identities that bind together rather than fragment Afghanistan. It gives those outside Afghanistan a stake in its success and provides Afghans with confidence that their country is again on a path of development that will improve their lives and provide basic security for their families.

Second, efforts must be focused on where the probability of success is highest. This sounds obvious, but much practice since 2001 has belied this insight. The Afghans and their international partners do not have unlimited money, people, skills or time. Given the scale and scope of the challenge, the industry priorities are clear: natural resources, agriculture, construction, trade and related services, and light industry. Some regions have more potential than others. The Afghan economy’s future will depend disproportionately upon favourable developments in a few urban areas, transit routes and border crossings. Many of these opportunities have been analysed and highlighted before, but basic improvements have not been implemented on a consistent, sustained basis.133

This leads to a third implication – that these national and local industry priorities must be integrated into a coherent plan of specific initiatives that are then driven down to the local level and sustained.134 Infrastructure is rightly recognised as important. The infrastructure level in Afghanistan was so poor after decades of destruction and neglect that almost any investment would produce some positive return. But, all else being equal, future infrastructure projects – such as investments in electricity – should be more closely integrated with priority industry development to maximise impact. Likewise, technical assistance and policy reform initiatives should prioritise certain industries. For instance, mining laws, regulations and procedures will likely have to be changed to provide the right incentives and security to outside investors to accelerate the development of revenue-producing fields.135 In some cases, direct grants will be appropriate to help Afghan companies capture value through more efficient practices and by moving into higher-value-added processes. Others will benefit most from business-to-business linkages to build skills, find new markets and attract international investors. Together, the consistent pursuit of strategic priorities is needed – rather than a “let a thousand flowers bloom” approach – to achieve results in such a challenging operating environment.

Fourth, there is a need for a new operating model. Today, the execution of international assistance is incredibly fragmented. Programmes and responsibilities often overlap. It is not clear who is in charge, or what is the appropriate division of labour. In the US agriculture effort alone, there have been US Department of Agriculture advisers, the military’s agricultural development teams (ADTs) and CERP-funded projects, provincial reconstruction teams and district support teams staffed with State Department and USAID personnel who may be involved in agricultural programmes, trade experts at Kabul embassy, and so on. This is just one donor in one sector, and does not take into account the slew of NGOs and development organisations of other countries (e.g., British, Canadian, German, Italian and Scandinavian). The regular rotation of civilian and military staffs further exacerbates this problem, as institutional memory and working relationships have to be constantly recreated. Furthermore, the international civilian presence throughout Afghanistan is likely to be reduced during the transition – including the end of PRTs and other assistance channels. This all suggests the need to move to a much lighter “footprint”. And without a greater focus on continuity, coordination and communication of efforts among the international players, confusion and duplication will continue.

Fifth, programme design and implementation must provide the right incentives to escape the short-term mindset that too often dominates the international community’s approach to Afghanistan. The cliché is sadly true – we have fought a dozen “one-year” wars since 2001 in large part because that is what those in the field are encouraged to do. A concern with programme monitoring and audits has led some USAID contractors, for instance, to avoid some important long-term projects because their impact would only be felt – and be measurable – after their period of contract performance had ended.136 Military commanders are sometimes judged by how rapidly they spend their CERP funding, not how wisely. The endless pursuit of “quick wins” is ultimately a losing proposition.

Lastly, the international community needs to rethink its existing models of public–private partnerships in Afghanistan. The Aynak copper mine is an instructive case in point. Putting aside allegations of corruption, the Chinese put together a better offer than other international bidders because they successfully integrated business investment alongside more traditional economic development assistance. From the vantage point of Afghan economic development, it may not matter whether the investment comes from China or India or Europe or the United States, unless a particular investment has negative internal or regional political ramifications. But from the NATO perspective, our statecraft would be strengthened if donor governments could more closely coordinate and even collaborate across the public–private sector line in such complex contingencies.137

In the US government today, for instance, there is no clear owner for the promotion of private sector development in Afghanistan – nor, more generally, to support economic stabilisation missions around the world. To consider just three efforts from across the US government, USAID’s private sector development programme is a relatively small part of the overall USAID effort, the Department of Commerce’s Iraq and Afghanistan Task Force lacks resources and bureaucratic clout, and the Department of Defence’s Task Force for Business and Stability Operations is an ad hoc, temporary body. Significantly, the Task Force had proven to be ecumenical in its approach, facilitating US and non-US companies’ relations with the local business. Non-Western companies will often have greater knowledge of the market, tolerance for risk, and therefore, willingness to operate in countries such as Afghanistan. Thus, cooperating with Western and non-Western companies is a necessary innovation that puts the mission ahead of any one country’s narrow economic interests. The time has come to consider establishing more robust, enduring, expeditionary capabilities whose missions would be to facilitate private sector engagement and development in fragile and conflict-affected states. Afghanistan during its transition could be its first stop.

The international community’s future operating model should be centred around the Afghans themselves – the entrepreneurs, educators, business owners, workers and government officials. Ultimately, they will be the real owners and drivers of any sustainable success in the private sector.

Getting the economic dimension right is, by itself, not sufficient for Afghanistan’s successful transition. Improved governance and security, among other factors, are self-evidently vital as well. But the economic fate of Afghanistan will hinge on private sector development. The international community cannot afford to take its eye off private sector development in this phase of the struggle for the future of Afghanistan. The reduction of the international community’s presence in Afghanistan leading up to the formal 2014 transition poses significant challenges to the Afghan economy. But it presents opportunities too – foremost among these is the opportunity to reduce not only the Afghan economy’s dependence on international aid, but also the distorting effects of that spending. With perseverance, support, and some luck, Afghanistan could return to a more “normal” path of development in the coming decade.138