Civil Rights and ProtestsSlavery and Anti-Slavery |

What did lawmakers do to resolve the slavery question before the Civil War? |

The mid-1800s were a trying time for the nation—the divide widened between the Northern free states and the Southern slave states, which were growing increasingly dependent on agricultural slave labor. Government tried but was unable to bring resolution to the conflict over slavery. Instead, its efforts seemed geared toward maintaining the delicate North-South political balance in the nation.

After the Mexican War (1846–1948), the issue was front and center as congressmen considered whether slavery should be extended into Texas and the western territories gained in the peace treaty of Guadalupe Hildago, which officially ended the war. Lawmakers arrived at the Compromise of 1850, which proved a poor attempt to assuage mounting tensions: the legislation allowed for Texas to be admitted to the Union as a slave state, California to be admitted as a free state (slavery was prohibited), voters in New Mexico and Utah to decide the slavery question themselves (a method called popular sovereignty), the slave trade to be prohibited in Washington, D.C., and for passage of a strict fugitive slave law to be enforced nationwide.

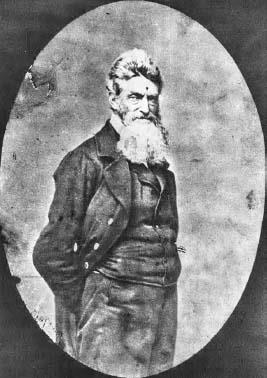

Four years later, as it considered how to admit Kansas and Nebraska to the Union, Congress reversed an earlier decision (part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820) that had declared territories north of the Louisiana Purchase to be free, and set up a dangerous situation in the new states: The slavery status of Kansas and Nebraska would be decided by popular sovereignty (the voters in each state). Nebraska was settled mostly by people opposing slavery, but settlers from both the North and the South poured into Kansas, which became the setting for violent conflicts between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces. Both sides became determined to swing the vote by sending “squatters” to settle the land. Conflicts resulted, with most of them clustered around the Kansas border with Missouri, where slavery was legal. In one incident, on May 24, 1856, ardent abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859) led a massacre in which five pro-slavery men were brutally murdered as they slept. The act had been carried out in retribution for earlier killings of freedmen at Lawrence, Kansas: Brown claimed his was a mission of God. Newspapers dubbed the series of deadly conflicts, which eventually claimed more than fifty lives, “Bleeding Kansas.” The situation proved that neither congressional compromises nor the doctrine of popular sovereignty would solve the nation’s deep ideological differences regarding slavery.

Abolitionist John Brown, who advocated armed conflict against those who were for slavery, led his followers into two battles against government forces in Kansas in 1856, killed five people in Pottawatomie, and was captured trying to raid an armory at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. He was convicted and hanged in 1859.