Arts and EntertainmentArchitecture |

What early African-American architect of acclaim helped to build Tuskegee Institute? |

The historical voices of people of color are those of an oppressed people who were forced from Africa to the Western Hemisphere, constituting a massive population shift. Beginning in 1619, they “came in chains” on their journey across the Atlantic Ocean, on a route referred to as the Middle Passage. Some claim that as many as twenty-five million came, several generations of people ripped from their homelands. From the seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth century they added to the riches of their European and American captors and owners.

It was not until 1807 that Great Britain, deeply entrenched in the African slave trade, ended such commerce in that country. The trade was outlawed only as a result of the growing number of abolitionists who argued that slavery was immoral and violated Christian beliefs. Yet, slavery throughout the British Empire continued until 1833, when the great anti-slavery movement was finally successful. In the United States, however, the slave trade was prohibited, but slave ownership was allowed to exist. In 1808 the slave trade as it had been known officially ended and was outlawed throughout the Americas.

Throughout the period of slavery, many anti-slavery efforts took place. Leading journalists, merchants, and influential men and women, black and white, slave and free, joined in the efforts. Many belonged to groups such as the American Anti-Slavery Society, the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, and similar organizations. Women also had their own groups, such as the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society. Great orators, like abolitionist and escaped slave Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), were quite vocal in the movement at home and abroad.

Equally well known among the efforts to end “the peculiar institution” called slavery was the Underground Railroad, a network to emancipate slaves. Its most ardent leader was abolitionist, nurse, Union spy, and feminist Harriet Tubman (c. 1820–1913), sometimes called “the Moses of her people.” Tubman made at least fifteen trips from North to South and led over three hundred of her people from bondage to freedom. Of equal importance was Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), abolitionist, women’s rights activist, lecturer, and religious leader, who was also an uneducated slave known for her rigid opposition to slavery. She had an articulate and a fearless voice in the promotion of liberal reform in race and gender.

So determined were some slaves to crush the “peculiar institution” that they tried to force change by engaging in insurrections. Some historians believe that these efforts were far more widespread than records show, yet they acknowledge leading efforts of such men as Nat Turner (1800–1831) in Southampton, Virginia; Denmark Vesey (1767–1822) in Charleston, South Carolina; and the efforts of ardent white abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859), who led a violent raid in Kansas on May 14, 1856.

From 1861 to 1865, a bloody war raged between the Confederacy and the Union, known as the Civil War, which, among other issues, prompted President Abraham Lincoln to make a proclamation to emancipate slaves. On January 1, 1863, the official Emancipation Proclamation was issued, and on January 31, 1865, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery throughout the states. Even so, the Confederate states refused to free their four million slaves until April 9 of that year. The news reached some states much later, meaning that former slaves, particularly those in Texas in 1865, had no idea that they were legally free. In June of 1865, Union General Gordon Granger, along with two thousand Union troops, arrived in Galveston, Texas, to take possession of the state and force compliance with the Emancipation Proclamation. African Americans began to celebrate the date of their freedom, or what they call Juneteenth; they honored June 19, the date on which they learned of their new status. Juneteenth has since become a day of celebration among many black Americans throughout the nation.

The Reconstruction period—a twelve-year period from 1865 to 1877—followed the Civil War and was a time to rebuild the South. The South lay in ruins and food and supplies were scarce. Blacks were homeless, cities destroyed, and government was nonexistent. Slowly, efforts followed to aid in the rebuilding, such as the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 to enfranchise blacks, although it was not until 1875 that the act became law. In 1883, however, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the law. Meanwhile, efforts of agencies such as the Freedmen’s Bureau, or the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, created in 1865, aided in uniting black families, built over forty hospitals, distributed food to the needy, and established 4,239 schools for blacks, including several historically black colleges. Even so, the bureau ceased to exist in 1868, because of Congress’ feeble efforts and a lack of a national commitment to provide equal citizenship for blacks.

Among other laws that addressed the civil rights of black people was the Plessy v. Ferguson decision—often equated with “separate but equal” provisions—that for almost sixty years served as the legal foundation and justification for keeping the races separated. This law existed until 1954, when it was overturned with the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision, which denied legal and unequal segregation in schools and public places.

Race relations left much to be desired, however, and a number of protests preceded the modern Civil Rights Movement. Protests were seen in Memphis (1866); Hamburg, South Carolina (1873); New Orleans (1874); Atlanta (1906); Springfield, Illinois (1908); Houston (1917); Tulsa (1921); Harlem (1935 and 1943); Detroit (1943); and elsewhere. Freedom’s call extended from the work of the abolitionist crusaders to the work of civil rights activists and leaders throughout the centuries. Such crusaders have included W.E.B. Du Bois, A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr., and Ida Wells-Barnett. Then came the modern Civil Rights Movement, which represented a time when African Americans had had enough and new protests swung into action. Led by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., the movement followed a policy of peaceful protest and included boycotts, marches, sit-ins, and other demonstrations. Included were the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955, the Albany, Georgia, movement, and the sit-in movement, including those of national prominence—the Greensboro, North Carolina, sit-ins and the Nashville, Tennessee, sit-ins. There were protests such as Freedom Summer (an intensive voter registration project in Mississippi), Freedom Rides, the famous March on Washington in 1963, and the Poor People’s March on Washington in 1968. The period saw the rise of the black power movement and greater racial pride, both stimulated by the work of activist Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Turè).

In addition to King, the various movements catapulted others into prominence, including Hosea Williams, John Lewis, Diane Nash (Bevel), Rosa Parks, Ella Baker, Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Turé), James Farmer, and a number of other sung—and unsung—heroes. These actions helped to spur on the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which helped to remove barriers to equal access and opportunity affecting blacks, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which guaranteed the voting rights of black Americans.

Organizations such as the Niagara Movement, the NAACP, and the National Urban League, helped to dismantle segregation, support education of blacks, address issues of housing, promote jobs and economic development, address issues of health in the black community, and promote black leadership. The federal government had taken some steps to promote racial justice, as seen, for example, in the work of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, a bipartisan agency established in 1957 as a temporary, independent agency. It continues to investigate citizens’ complaints about violations of voting rights and other fraudulent practices. In 1997 President Bill Clinton established the Initiative on Race in an effort to move the nation closer to a stronger, unified, and more just America. Black America has not forgotten the ills that their ancestors endured, many calling for the federal government and white America to pay reparations, or compensation, for being wronged. The idea has been discussed many times; for example, near the end of the nineteenth century former Tennessee slave Callie House became a leader in a movement to petition the U.S. government for pensions and reparations for African Americans held in involuntary servitude. During the Civil Rights Movement, leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee issued a “Black Manifesto,” insisting on reparations for African Americans. In 1990 the idea of reparations gained currency with some of the American public.

The hold that America had on enslaved black Americans failed to thwart blacks from seeking their own cultural agenda. They came from Africa with musical and artistic talents, giving full expression to their creativity on the slave plantation. Dance, music, and song were entrenched in African societies and used in religious ceremonies and rites. Now in America, these cultural expressions enabled slaves to shape the black community by entertaining themselves as well as their masters. Their shout, or ring shout, was an example of an artistic form from their African background. In music as well, talented slaves demonstrated their skills. Slave musicians played violin, flute, piano, and sang; some gave public concerts. For example, in 1858 Thomas Greene Bethune, also known as “Blind Tom,” performed before President James Buchanan at the White House and received national fame as a pianist.

African Americans are also known for their religious songs, or spirituals, and began to sing them from the time they were first enslaved. Sometimes called sorrow songs, some also call them the most prominent style of Southern slave music. The development of the spiritual is difficult to trace, for the music was not recorded at first, but preserved and passed on orally; it probably emerged in the late 1770s and became prominent between 1830 and the 1860s. The spiritual represented a shield against the inhumanity of slavery, as slaves endured the pain of work on the plantation and sought routes to freedom either through an unknown being that would carry them out of slavery or through a more earthly method of escape. Slave songs often had hidden messages, such as use of the Jordan River as a “river of escape.” Beginning in 1882 the Fisk Jubilee Singers from Nashville’s Fisk University began to popularize spirituals by singing them during their tours across America and in England.

The music of African Americans was presented later on through big bands, in concert halls, through their own compositions, and in musical forms such as jazz, the blues, gospel, and soul. Certain eras in history saw the effects of African Americans and their music on cultural developments. For example, during the modern Civil Rights Movement, songs of protest and progresses re-emerged or were written, and were sung in marches and rallies to inspire protesters and to send messages to others. The song “We Shall Overcome” became the theme song of the movement, yet this spiritual was actually a song from the early anti-slavery movement. From Bessie Smith to B. B. King, the soul of black America has been presented in song.

Slave artisans were also skilled in their work as painters, silversmiths, cabinet-makers, and sculptors. Some worked in iron and others with metals during the eighteenth century, and their work was seen in Southern mansions, churches, and public buildings. Names of many of these artisans remain unknown. Leading painters from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries include Edward Mitchell Bannister, Meta Warrick Fuller, Edmonia Lewis, and Henry Ossawa Tanner.

Perhaps no other era in African-American history has been preserved and studied more than the Harlem Renaissance period, also known as the Negro Renaissance and the New Negro Movement. This literary, artistic, and cultural revolution was centered in the Harlem section of New York City, particularly during the 1920s. There were precursors of the movement as well as intense cultural developments after that time. James Weldon Johnson is an example of a precursor as well as a Harlem Renaissance luminary. Among the leading writers of this period are Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, Jessie Redmon Fauset, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, and Jean Toomer. Visual artists were also important, including Aaron Douglas, Meta Warrick Fuller, and Augusta Savage. Actors like Charles Gilpin, independent filmmakers such as Oscar Micheaux, and dancer and actor Florence Mills helped to round out this group of luminaries. After World War II, and into the modern Civil Rights Movement, some artists depicted black migration from the South to urban areas in the North in their works. Such artists included Romare Bearden, Beauford Delaney, and Jacob Lawrence. As well, Walter Williams, Sam Gilliam, David Driskell, Faith Ringgold, and Elizabeth Catlett Mora often embodied their personal stories into their work. Some artists moved their works to the streets of the ghetto, as graffiti became popular and developed a market value. Photographers Gordon Parks and Moneta Sleet chronicled black history through the camera.

By the 1930s organized efforts of the federal government helped to encourage and support black artistic talent. The Works Progress Administration and the Federal Theater Project employed many African Americans to work in plays, contemporary comedies, circuses, and in films. Katherine Dunham, Rex Ingram, and Butterfly McQueen were among the dancers and actors who benefitted. Two major black theater projects emerged in the wake of the Federal Theater Project: the American Negro Theater and the Negro Ensemble Company. Later, playwrights Lorraine Hansberry and August Wilson became prominent. By the late 1990s, Tyler Perry reached an untapped audience and was rocketed to enormous success. During the last century, African Americans also emerged as cartoonists and radio show hosts. Much of black America’s culture is showcased at national black theater and art festivals.

Although not all African Americans were enslaved, much of the information about African Americans as entrepreneurs has been handed down through slave narratives. The talents of both free and enslaved blacks, however, were legion. Free blacks had many more opportunities to develop businesses than those enslaved and maintained many businesses outside the South. As early as the 1700s, records show that Stephen Jackson of Virginia made hats of fur and leather. Before the Civil War, there were landowners, brokers and merchants, a tailor, a grocer, and a lumber and coal merchant. One prominent name among the wealthy African Americans was William Alexander Leidesdorff (c. 1811–1848), a trader, rancher, landholder, hotelier, ship captain, and steamboat innovator. The leading black antebellum entrepreneurs included cotton planters, a sail maker, a barber, a sugar planter, and a commission broker. By the Civil War period, the combined wealth of free blacks exceeded $100,000, a respectable amount at that time.

Notable among slave-born entrepreneurs is William Tiler Johnson (1809–1851), who became known as the “Barber of Natchez”; he was especially popular among white Americans. Until the late nineteenth century black barbershops with large white clientele fared well. During the lifetime of the African-American community, both barber shops and beauty shops have been successful industries. Those shops that survived in the racially segregated South, however, often catered to whites. Icons of the black beauty industry are Madam C. J. Walker (1867–1919), Sarah Spencer Washington (1889–1953), and Annie Turnbo Malone (1869–1957). In addition to manufacturing companies that these women founded and owned, they established beauty schools and revolutionized the care of black hair. In later years, the Cardozo sisters, Rose Morgan (1912–2008), and Joe L. Dudley (1937–) became prominent salon owners, stylists, and/or owners of manufacturing companies. Barber shops and beauty shops became vital to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and were political incubators for politicians and civil rights workers who needed a safe haven in which to plan and promote their work.

The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), founded by journalist and activist Marcus Garvey (1887–1940), was well known for promoting economic development in the black community. Garvey also launched a shipping company and established other business organizations that employed many blacks. He also founded a tailoring business, grocery stores, restaurants, a doll factory, and other ventures that brought him phenomenal success.

Among other businesses that supported economic development in the African-American community is the funeral business. Following the Civil War, the funeral business emerged as a one-person operation and later grew into a family business. This industry was highly successful up to the 1980s, when inflation took its toll, and many firms closed their doors. Others, however, merged and remained successful. Some funeral establishments owned burial associations, insurance companies, cemeteries, and other services.

Black business districts in two cities became known as “Black Wall Street.” In the first decades of the twentieth century, Durham (North Carolina) and Tulsa (Oklahoma) each had a number of flourishing businesses owned and operated by blacks. In Durham, these included the well-known North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company as well as cafes, movie houses, barber shops, boarding houses, grocery stores, funeral homes, and other traditional services. Tulsa offered hospitals, libraries, churches, grocery stores, a bus line, construction companies, and other ventures. The golden age of black business development came during the first half of the twentieth century, as blacks in many areas served a segregated market with businesses such as real estate, hotels, homes, theaters, railroad lines and other transportation systems, automobile repair shops, banks, and loan associations.

Not to be overlooked is the banking business and the leadership that African Americans provided in that area. While the federally founded Freedman’s Bank (or the National Freedman’s Savings Bank and Trust Company), established in 1865, aimed to serve the financial needs of African Americans, it was privately owned by whites. In 1888 the nation saw the first black-created and black-run banks: the True Reformers’ Bank of Richmond, Virginia, and the Capital Savings Bank of Washington, D.C. In 1903 Maggie Lena Walker (1865–1934) founded the Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank in Richmond, Virginia, and became the first black woman bank president in the nation. Her bank survived the Great Depression and continues to function today.

The African-American community has been the source of many self-help programs, such as consumer cooperatives. Spurred by union leader A. Philip Randolph in Harlem and the Housewives League of Detroit, they began to evolve after World War I. The Colored Merchants Association was a notable example of a consumer cooperative. Founded in 1928, the cooperative was a voluntary chain consisting at first of twelve members who operated their grocery stores as “C.M.A.” stores. Soon the organization spread to other states, with its national headquarters in New York City. The organization began to decline in the 1930s.

Economic boycotts and protests have a long history in black America and date back to 1933, when the National Negro Congress resolved that black business should not buy or sell products that were slave-made. Between 1900 and 1906, blacks in over twenty-five Southern cities protested against segregated seats on street cars. Similar economic protests and economic withdrawals continued and became more widely known during the sit-ins and freedom rides of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Jobs for blacks, promoted through the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign that began in 1929, were a forerunner of the economic protests of the Civil Rights Movement.

The food service industry (including soul-food restaurants), insurance companies, manufacturing, publishing, and other ventures have brought prominence to the black community. To protect the rights of workers in segregated work situations, black union leaders such as A. Philip Randolph, George Ellington Brown, and Addie L. Wyatt emerged. Black women have prospered as entrepreneurs as far back as the 1860s. Some leaders include Christiana Carteaux Bannister (1819–1902), who operated a “Shampooing and Hair Dyeing” business in Massachusetts and Rhode Island; slave-born nurse and midwife Biddy Mason (1818–1891), the first known black woman property owner in Los Angeles; and women of the hair-care industry, such as Madam C. J. Walker and Annie Turnbo Malone, who both became millionaires.

The educational, economic, social, and cultural needs of the African-American community have been addressed by a number of organizations focused on meeting these needs. Since many of these organizations were founded during the time of widespread racial segregation, they addressed issues that advanced the black race. While the exact year in which black organizations were first founded is unknown, it has been established that in 1787 the Free African Society was founded, becoming the first black organization of note in this country. Grouped by type, these organizations include abolitionist, business, civil and human rights, educational, financial, funeral, journalism, medical, political, social, religious, and women’s groups. The National Negro Business League, organized by educator and school-founder Booker T. Washington in 1900, had various initiatives, among them to help black people establish new ventures and to bring about black economic independence. In the 1920s many African Americans worked wherever they could to meet financial needs; thus, they took jobs with companies such as the Pullman Palace Car Company. They endured numerous injustices in employment, which led them to unite in protest. In 1925 A. Philip Randolph organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first major nationwide black union, but many years would pass before the Pullman Company actually accepted their collective bargaining plan. In time, other unions were established to ensure equal benefits in employment between white and black workers.

While not a black organization, the American Missionary Association was established in 1846 with an aim to form overseas missions for freed slaves. Soon the AMA turned its efforts to abolitionist and educational activities within the United States. From 1850 until the end of the Civil War, the AMA established over five hundred schools for blacks and whites in the South. Later the AMA founded several black colleges. The need to promote the civil rights of African Americans led to the establishment of such organizations as the National Equal Rights League in 1864, the National Afro-American League in 1890, and the Niagara Movement in 1905, which was the forerunner of the NAACP (founded in 1909). In 1910 the Committee on Urban Conditions Among Negroes was founded and, in 1911, became the National Urban League. Its purpose was to secure civil and economic opportunities for black people. When the modern Civil Rights Movement began in the 1950s, blacks saw a need to establish organizations to promote nonviolent and direct-action attacks on segregated America. Thus, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference grew out of the 1955–1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott and worked to appeal to the moral conscience of those who supported racial segregation. A youth political organization was also organized in 1960 and became known as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which helped students to become involved in the fight for equal rights.

Those organizations formed as learned societies to promote professional study of black history and culture included the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, co-founded in 1915 by Carter G. Woodson; in 1976 it was renamed the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. The organization sponsored the first Negro History Week in 1926; since 1976, the week-long celebration has been renamed Black History Month. In the educational arena, the United Negro College Fund began in 1944 in response to the need to address economic conditions of private black colleges. It continues to exist, with support from various philanthropic organizations. A few black colleges have been recognized for their academic excellence and granted chapters of Phi Beta Kappa, a prestigious honorary society for undergraduate achievement in the humanities. The first chapter was established at Fisk University on April 4, 1953, followed by a chapter at Howard University four days later.

There are also black fraternal, social service, and religious organizations founded for blacks. Among these is Sigma Pi Phi (or the Boulé) for men who have made a place for themselves in the community and black fraternities and sororities (or Greek-letter organizations), once social organizations and now service-oriented. These include the oldest—Alpha Phi Alpha—established in 1906; Omega Psi Phi, Kappa Alpha Psi, and Phi Beta Sigma. Black women’s sororities include Alpha Kappa Alpha (the oldest, founded in 1908), Delta Sigma Theta, and Zeta Phi Beta. Undergraduate chapters exist on college campuses, while graduate chapters are within many communities. In addition to these organizations, the medical community organized the National Medical Association in 1895 and the National Dental Association, which was founded in 1932 with the merger of several dental associations. Among those organizations founded for black women are the National Council of Negro Women, which educator Mary McLeod Bethune helped to form in 1935; from 1957 to 1998 the organization was headed by nationally known community servant Dorothy Irene Height. The Links, Inc. was established in 1946 as an international not-for-profit corporation for women. It is one of the largest and oldest volunteer organizations in the country.

African Americans have long seen a need to create their own political agenda, primarily as a means of securing their equal rights. While a few blacks, such as Henry Highland Garnet, Charles B. Ray, Samuel Ringgold Ward, and Frederick Douglass, had been involved in national political gatherings as early as 1843 and 1866, and one (Douglass) was nominated as a vice presidential candidate at the Republican Convention in 1872, much more political action came during the Reconstruction (the twelve-year period following the Civil War). During this period, black Americans were represented at every level of government, at the local, state, and federal levels. The nation saw blacks as postmaster, deputy U.S. marshal, treasury agent, federal office clerks, on county governing boards, police juries, and boards of supervisors. In 1868 John Willis Menard (1839–1893) was the first black elected to Congress. Between 1879 and 1901, more than one thousand African Americans were elected to local and state office. There were six lieutenant governors and one governor. In Louisiana, P.B.S. Pinchback (1837–1921), became the first African-American governor; he was appointed to the post but defeated in elections in 1871. He remained the nation’s only black governor until 1989, when L. Douglas Wilder was elected governor of Virginia.

The Great Migration, which occurred from about 1880 to 1970 (with a break between 1930 and 1940), saw blacks move from the South to urban centers in the North, to Kansas, and other Midwestern states. They also settled in major cities, such as New York, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles. They migrated because of economic desperation, racism, and difficult living conditions. The Republican Party was the party of choice by most African Americans until the 1930s, when blacks became alienated from that party and U.S. President Herbert Hoover. After Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, certainly by his second run in 1936, blacks switched their support in his favor and toward the Democratic Party.

President Roosevelt established a network of African-American advisors who became an informal body known as the “Black Cabinet.” This group represented black interests and concerns during the Great Depression and the New Deal economic recovery programs of the 1930s. Members included journalist Robert L. Vann, law school administrator William H. Hastie, National Urban League executive Eugene Kinckle Jones, educator Mary McLeod Bethune, and Ralph Bunche (later of United Nations fame). Blacks also gained considerable political clout during the Roosevelt administration, becoming specialists and advisors in a number of governmental departments. During President Bill Clinton’s administration, a record number of African Americans joined his cabinet. These included secretary of commerce Ron Brown, energy secretary Hazel R. O’Leary, U.S. surgeon general Joycelyn Elders, secretary of agriculture Michael Espy, and secretary of transportation Rodney Slater.

President George W. Bush appointed fewer African Americans to top positions than Clinton. His appointees include Colin Powell (as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and later secretary of state), secretary of education Rodney Paige, secretary of housing and urban development Alphonso Jackson, and secretary of state Condoleezza Rice.

African Americans have made inroads in the federal courts; for example, Thurgood Marshall (1908–1993) became the first black associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967. Clarence Thomas was named to the court in 1991, becoming only the second black associate justice of that court. Black women have made their mark on the political scene as well. In 1996 Constance Baker Motley (1921–2005) was the first black woman federal judge, serving on the U.S. District Court, the Southern District of New York. Women have served as mayors of cities and in the U.S. Congress.

Most historic among the political accomplishments of African Americans was the election of Barack Obama to the U.S. Presidency in 2008, and his reelection in 2012, making him the first of his race elected to the highest office in the nation. He was catapulted onto the national political scene in 2004, after giving a stirring keynote address before the Democratic National Convention. During his campaign for the presidency, he garnered financial support from small donations solicited over the Internet and used blogs and other nontraditional media avenues to change the way political campaigns are conducted. His campaign for reelection was characterized by smart political moves by his advisors, such as door-to-door voter solicitations in unexpected neighborhoods and a demonstrated record of uplifting the national community, particularly its economic conditions.

Religion has been an important part of the African-American experience. From the beginning, Colonial America saw some slaves Christianized but soon questioned this practice because a number of Christian slaves successfully sued for their freedom. John Wesley and others became sympathetic to their cause and needs. Others who brought the gospel to slaves included Harry Hosier, also known as “Black Harry”; he was the first known black Methodist preacher. The African influence was seen early in the family structure, funeral practices, and church organizations of black Americans. As early churches during slavery were segregated, informal black churches, called “hush harbors” or “bush arbors,” were gradually established. These were hollows or remote and inconspicuous places in the slave community where slaves, led by slave preachers, worshipped God as they pleased and in a tradition that their masters never knew they had.

Independent black churches were founded by various religious denominations. The first black Baptist church was organized in 1758, in Mecklenburg, Virginia. Some say that such a church existed in Lunenburg in 1756, but this is unsubstantiated. The first black Baptist church under black leadership was formed in Silver Bluff, South Carolina, with David George, a slave, as its first black pastor. Andrew Bryan built the First African American Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia, in 1794. Methodist societies also held revivals and some churches had racially mixed memberships. Many early black Baptist and Methodist preachers were unable to read or write, and some of the earliest preachers and exhorters were former African priests who had leadership and persuasive abilities. Their services were emotionally charged and filled with imagery.

Leaders of the African American Episcopal Church included Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, who left a white congregation in Philadelphia and formed the Free African Society. Then Allen organized Bethel Methodist Church in Philadelphia in 1794. Allen later became the first black bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church; he sanctioned the inclusion of women in the ministry and authorized Jarena Lee to be an exhorter in the church. His church, and many other black churches of that period, was a forum for abolitionists and anti-lynching campaigns. As blacks protested their ill-treatment, Henry McNeal Turner, a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, became the first black churchman to declare that God is black.

The black church has continued to believe in the importance of music, especially singing, in the worship service, saying that it is a magnet of attraction and serves as a vehicle of spiritual transport for the congregation. This is a carry-over from the West African diaspora where the music is vocal or instrumental. Some use African drums, while the use of spirituals in the black church has been perpetuated. Music in black churches popularly includes performances of groups of liturgical dancers. Gospel music has been promoted in the black church as well, and was greatly influenced by the work of Charles Tindley, at first an itinerant preacher who preached and sang at camp meetings in Maryland. Later he became one of the most powerful leaders in Philadelphia’s black community, speaking before black and white audiences. His Temple United Methodist Church became famous for concerts and new music, much of it written by Tindley himself. Other gospel composers of that period and later times include Sallie Martin, Roberta Martin, Lucie Campbell, Thomas Dorsey, and Mahalia Jackson.

A key to the success of the modern Civil Rights Movement was the black church and its leadership. Many remained at the forefront of the movement and were also leaders of such civil rights organizations as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Most prominent among these church leaders was Martin Luther King Jr. His “Letter from the Birmingham Jail” as well as his “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered at the 1963 March on Washington, became well studied and well quoted in many arenas. As well, his leadership of various protest marches in which he literally put his life on the line before staunch segregationists attested to his full support of equal rights for all people, but particularly blacks.

Black megachurches have emerged during the last two decades of the twentieth century. Their leaders—many of them charismatic preachers and speakers—include T. D. Jakes, Creflo Dollar, Eddie Long, and Frederick K. C. Price. Jakes is said to be the best known among the megapreachers and now has celebrity status as well as material success. In addition to these churches and the various religious denominations of note, some blacks have joined the Jewish faith. In 1906 Pentecostalism began to spread in the black community. Some black church leaders advocated Black Nationalism; for example, men like Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, Marcus Garvey, Elijah Muhammad, and Malcolm X popularized the movement. It was about 1914 that M. J. “Father” Divine, or George Baker, and William J. Seymour promoted the traditions of the Pentecostal movement. The Rastafarianism movement began in the early 1930s; it was founded in Jamaica and is based on interpretations of the Bible and repatriation to Africa. Muslims in America follow the traditions of Wallace Fard, who in 1930 organized the group that became Temple No. 1 of the Nation of Islam in Detroit.

Women of righteous discontent emerged early on and were vital leaders of the community, sometimes serving as traveling evangelists. After being denied access to the pulpit for many years, women finally emerged as leaders. These included Sojourner Truth, Zilpha Elaw, and Jarena Lee. The first largely black Shaker family in Philadelphia was founded by Rebecca Cox Jackson. Since 1984 the nation has seen black women bishops—Leontine T. C. Kelly in the United Methodist Church, Barbara Clementine Harris in the Anglican Church, Vashti McKenzie in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Teresa Elaine Snorton of the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. Since the 1970s, as women sought equality and many joined the feminist movement, there began a trend called woman’s theology. The term was derived from the “Womanist” theory of writer Alice Walker, who believes that the experiences of black women and white women are vastly different. Some say that it is similar to black theology, or the hope and liberation of women or of black people.

African Americans have changed the world through their contributions to science, medicine, inventions, and aviation. Names such as Benjamin Banneker, who issued almanacs and helped to survey the national capital, and George Washington Carver, who derived hundreds of products from peanuts, sweet potatoes, and pecans, are commonly and rightfully known. What are perhaps less well-known are the inventions of slaves and free blacks who lived much earlier. Since slaves were forbidden from receiving patents, their inventions went unrecorded, and patents were assigned to their masters instead. Free blacks were able to record some of their inventions; for example Henry Blair patented a corn or seed planter, Thomas Jennings invented a dry-cleaning process, and Augustus Jackson improved the process for making ice cream ice cream (his work was not patented). In 1781 Peter Hill became America’s first known black clockmaker. Published works often promote the work of Norbert Rillieux, whose inventions were of great value to sugar-refining; Elijah McCoy, who patented several lubricators for steam engines; Lewis Howard Latimer, who patented the first cost-efficient method for producing carbon filaments for electric lights; and Garrett A. Morgan, the first black to receive a patent for a safety hood and smoke protector. The implantable heart pacemaker that Otis F. Boykin invented has helped to save and lengthen the lives of thousands of men and women worldwide. Black women have achieved as inventors as well; for example, Marjorie Stewart Joyner patented a permanent waving machine and, in more recent years, Patricia E. Bath discovered and invented the laserphaco probe, a new device for cataract surgery.

The history of African Americans in medicine shows that slaves, who lived in unsanitary conditions, were concerned about their health and used their homeland knowledge of herbs, barks, and other items found in everyday life to create cures. Herb or root healers dispensed medicine for the treatment of slaves and their masters as well. In addition to the self-trained practitioners during the slavery period, early black physicians, some of them self-taught and others trained by apprenticeship, included David Ruggles, William Wells Brown, John Sweat Rock (also a lawyer), and Martin Robison Delany. Those professionally trained included James McCune Smith and Alexander Thomas Augusta. Some physicians graduated from what was known as the Eclectic Medical College in Philadelphia, which was composed of physicians in pre-Civil War America who believed in native remedies such as plants and herbs. The nation continues to acknowledge Daniel Hale Williams, who performed the world’s first successful heart operation in 1893, as well as Charles Richard Drew, the first person to set up a blood bank, in 1940. Benjamin Solomon Carson gained international acclaim in 1987 when he and a seventy-member surgical team successfully separated seven-month-old West German twins who were conjoined at the back of the head. A number of black medical schools were established, soon after the Civil War. Howard University was the first historically black institution to establish a medical school, in 1868. During the next four decades, at least thirteen other black institutions followed. Notable among these is Meharry Medical College, founded in 1876 and thus the oldest surviving black medical school in the South.

In aviation and space, one of the early black pilots in America was Eugene J. Bullard, who in 1917 flew for the French. Black women drew attention in aviation in 1921, when Bessie Coleman became the first African American woman to gain an international pilot’s license. She was also the first black woman “barnstormer,” or stunt pilot. The first black astronaut was Robert H. Lawrence Jr., in 1963. America’s first black astronaut to make a space flight was Guion (Guy) Bluford Jr. In 1986 Ronald McNair became the first black astronaut to lose his life during a space mission, when the space shuttle Challenger met disaster, exploding shortly after liftoff. Black women made their mark in space as well, notably Mae C. Jemison, who was named the first black woman astronaut in 1987. The world saw the first black commander to lead the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s shuttle Discovery mission in Charles Frank Bolden Jr., who also became America’s leading voice on space exploration when he was appointed to lead the NASA space program in 2009.

As Africans came to the New World, many brought with them athletic prowess. In Africa they had enjoyed many athletic contests, often connected to religious ceremonies, rites of passage, or simply entertainment for onlookers. They also had been taught general fitness to develop speed, endurance, and flexibility. They were taught economic survival (made possible, for example, through hunting and fishing), cooperative values (as seen in team work), and military skills (used to train warriors). As their bond servants’ sporting activities threatened to disrupt the daily life of the slaveholders, they made efforts to control and limit the slaves’ sports activities. Slaves were allowed to train gamecocks and horses, and to work in taverns. Then they were allowed to run races, swim, wrestle, box, and play ball games.

Before the Civil War, free blacks and slaves engaged in numerous sports, some of which drew large crowds of black and white spectators. Blacks were especially involved in horse racing, and the best jockeys and horse trainers were black. Slaves had grown up caring for horses and knew how to handle them. In the North, however, jockeys were imported from England or were local whites. The first jockey of any race to win the Kentucky Derby was Oliver Lewis, who won in record time in 1875. Thirteen of the fifteen jockeys in that race were black. The first jockey of any race to win the Kentucky Derby three times was Isaac Murphy (or Isaac Burns), who won 44 percent of all the races that he rode and was considered one of the greatest race riders in American history. When the Derby distance was trimmed from one and one-half miles to one and one-quarter miles in 1896, Willie (or Willy) Simms was the first winner at that distance.

Another sport that brought world fame to black sports figures was cycling. Marshall W. “Major” Taylor (1878–1932) was the first native-born black American to win a bicycle race, in 1898. Boxing has long been a popular sport and is said to have had a more profound effect on the lives of African Americans than any other sport. During slavery, masters often matched one strong black man against a peer from a nearby plantation. An example was seen in the boxing feats of Tom Molineaux (1784–1818). Although he defeated white boxer Tom Cribb to become the first black American boxing champion in England in 1910, his victory was never acknowledged because Londoners did not want the public to know that a black boxer had beaten a white. Other boxing greats included Bill (William) Richmond (1763–1829), who became prominent in England in 1805; George “Little Chocolate” Dixon (1870–1909), who won the bantamweight title in 1898 (and later the featherweight title) to become the first black world champion; Peter Jackson (1861–1901), known as the “black prince” and the “Black Prince of the Ring,” was called “the most marvelous fighting man of his time”; Jack Johnson, who became the first black heavyweight champion in 1908; Joe Louis (1914–1981), the “Brown Bomber” who became the first black national sports hero and the first black heavyweight champion since Jack Johnson; and colorful character Muhammad Ali (1942–), the first black prizefighter to gross more than a five-million-dollar gate and the first to win the heavyweight title three times. Others included Joe Lashley, Ezzard Charles, Sugar Ray Robinson Jr., Joe Frazier, Thomas “Hitman” Hearns, and George Edward Foreman. Black women boxers emerged as well, and included Laila Ali and Jacqui Frazier-Lyde, daughters of two boxing greats—Ali and Frazier.

Negro Leagues Baseball was popular prior to 1947, when the sport was racially integrated. Andrew “Rube” Foster, who played with, managed, and owned the Chicago American Giants, developed the Negro National League in 1920 in Kansas City, Missouri, and became known as the father of the Negro Leagues. The Negro National League, along with the Negro American League, had the most sustained success among black baseball leagues. During the heyday of the Negro Leagues, the best teams included the Kansas City Monarchs and the Homestead Grays. Players Leroy “Satchel” Paige, John Gibson, and James Thomas Bell (known as “Cool Papa”), became legendary. The Brooklyn Dodgers broke the color line in baseball, in 1947, when the team signed Jackie Robinson from the Monarchs. Other players of this era included Larry Doby, Don New-combe, and Roy Campanella. The move to integrated baseball signaled the demise of the Negro Leagues. Later, other star players of the sport included Henry “Hank” Aaron, Willie Mays, Reggie Jackson, and Barry Bonds.

Major league sports were slow to integrate. Professional basketball was not integrated until 1951, when the Boston Celtics drafted Chuck Cooper and the New York Knicks hired Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton. Among the big stars of a later period were Bill Russell, Wilt “Wilt the Stilt” Chamberlain, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Elvin Hayes, and Willis Reed. Then came Julius “Dr. J.” Erving, Moses Malone, Wes Unseld, Earvin “Magic” Johnson, Patrick Ewing, Charles Barkley, Shaquille O’Neal, Allen Iverson, Kobe Bryant, and LeBron James. The Harlem Globetrotters, founded in 1952, continues its show-stopping basketball games in national and worldwide events. Women’s basketball has become a popular attraction as well, through the work of legendary college coaches C. Vivian Stringer (1948–) and Carolyn Peck (1966–), and other women sports leaders.

Unlike other major sports, professional football began as an integrated activity and continued until 1930, when it changed to a segregated entertainment. A few black players were recruited in 1945; these included Woodrow Wilson “Woody” Strode, Kenny Washington, and Ben Willis. The number increased in the 1950s, with Jim Brown becoming a superstar for the Cleveland Indians in 1957. The Washington Redskins were the last NFL team to integrate. Other black football icons include Jim Brown, Alan Cedric Page, Herschel Walker, Walter Jerry Payton, Warren Moon, Jerry Lee Rice, Barry Sanders, and Marcus Allen. In the new millennium, the sport has seen Emmitt J. Smith III, Donovan McNabb, and the emerging icon Robert Griffin III (RG3). Professional football also began to hire black coaches. In 1989 Arthur “Art” Shell Jr. headed the Los Angeles Raiders, and in 2007 Anthony Kevin “Tony” Dungy led the Indianapolis Colts to the championship in Super Bowl XLI, defeating the Chicago Bears and his coaching friend Lovie Smith in the contest.

Pioneers in golf who won major professional championships have included Charlie Sifford, Lee Elder, and Calvin Peete. The most popular and accomplished black golfer is Eldrick “Tiger” Woods, who won the crown jewel of golf matches—the Masters, in Augusta, Georgia, in 1996—the first of his race to do so. He went on to become the first golfer ever to hold four major golf titles simultaneously—the U.S. Open, the British Open, the PGA championship, and the Masters again in 2001. Althea Gibson became the first black professional woman golfer in 1964.

African-American icons in other sports include Dominique Margaux Dawes, the first black woman gymnast to compete on a U.S. Olympic team; in 1996 she helped the U.S. women’s team win its first Olympic gold. The world rejoiced during the 2012 Summer Olympics, when Gabrielle “Gabby” Douglas, then only sixteen years old, became the first African American to win gold in the women’s all-around final competition. In tennis, several black athletes became legends. Ora Washington pioneered in the sport and was the first black woman to win seven consecutive titles in the American Tennis Association. Other tennis luminaries include Althea Gibson, Arthur Ashe, and Venus and Serena Williams. Black stars have dominated in track and field, including sprints, relays, long jump, broad jump, and triple jump. Perhaps best known among the icons is Jesse Owens, who in 1936 won four gold medals at the Berlin Olympics. Other icons include Ralph Boston, Carl Lewis, Rafer Lewis Johnson, Edwin Corley Moses, Michael Duane Johnson, and Maurice Greene. Alice Coachman Davis was the pacesetter among black women track stars, becoming the first to win Olympic gold at the 1948 Olympics in London. Wilma Rudolph overcame a serious disability to win three gold medals in the 1960 Olympics. The late Florence Griffith Joyner and her sister-in-law Jackie Joyner-Kersee are among the remaining women track stars. In other sports, Wendell Oliver Scott became a legendary race car driver; Willie Eldon O’Ree and Grant Fuhr excelled in hockey; Debi Thomas and Shani Davis were winners in ice skating; James “Bubba” Stewart dominated in motocross; and Phil Ivey became one of the world’s best all-round poker players. In rodeo, former slave Nat Love, known as “Deadwood Dick,” became the first known black champion; Bill Pickett developed bulldogging; and Fred Whitfield excelled in calf roping.

The voices of African Americans continue to tell the story that they have lived on America’s shores. They have spoken, and continue to speak, through their gifts and talents and have preserved much of the rich heritage that they brought with them from their motherland. The history of a people often cursed and despised has blossomed into the culture of a people of immense talent, determination, and endurance.

Among America’s early African-American architects is Robert Robinson Taylor (1868–1942). He was the first black admitted to the School of Architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1888 and the only black in the first-year class. After Taylor graduated, educator Booker T. Washington hired him as a teacher in the Mechanical Industries Department and as campus architect, planner, and construction supervisor for Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Taylor designed twenty-eight buildings for Tuskegee, including Booker T. Washington’s residence, known as “The Oaks,” and a laundry that later became the George Washington Carver Museum. In 1912 he prepared the first plans for the rural schools that philanthropist Julius Rosenwald funded under Washington’s request. Two years later he prepared plans for an industrial building and a teachers’ home for the rural schools project. Taylor also chaired the Tuskegee, Alabama, chapter of the American Red Cross—the only black chapter in the nation.

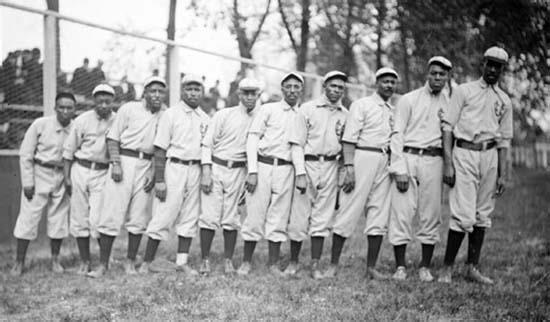

A 1911 photo of Chicago’s American Giants baseball team, the most successful team in the Negro Leagues from the 1910s through the 1930s. The team disbanded in 1952.