Science, Inventions, Medicine, and AerospaceMedicine |

What was the “Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment”? |

Historically, much medical experimentation has been enacted on poor people, both black and white. Between 1932 and 1972 the Public Health Service conducted what has been called “one of the most outrageous abuses of African Americans in this period”—a research project throughout Macon County, Alabama, that focused on patients with untreated syphilis. Participants included more than six hundred infected and uninfected black men. The men were primarily impoverished sharecroppers or day laborers. Treatment for syphilis was withheld even though penicillin was determined to be an effective drug for treatment of the disease. Participants were offered free medical care, free meals, expenses of burial, and other inducements that have been called unethical, but they were unaware of the risks, including possibility of death. There is no evidence to suggest that the men gave “informed consent.” The Public Health Service sought continued cooperation from the groups and thus worked through Tuskegee Institute (now University) in Alabama and the Tuskegee Veterans Hospital. Some one hundred men died, forty wives were infected, and nineteen children were born infected. The project became known by different names: the Tuskegee Study, the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, the Tuskegee Experiment, and the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male. By the 1970s, the study, previously kept silent, was made public, and it was discontinued in 1972. In 1974 the federal government initiated reparation payments to the few survivors. President Bill Clinton apologized to the eight who had survived until 1997, calling the actions of those responsible for the study “clearly racist.”

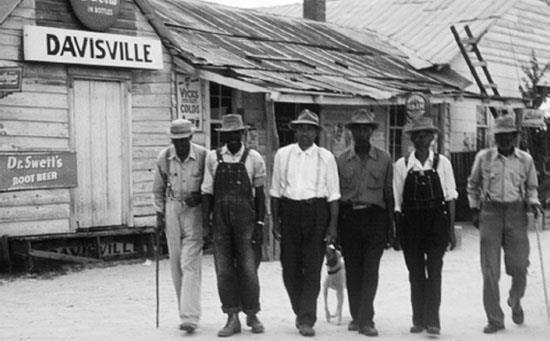

This is a group of men who were test subjects in the now-infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. In the 1970s, the truth about how men and women were the victims of a deadly experiment was released to the public.