Culture and RecreationFine Art |

How is Picasso’s work characterized? |

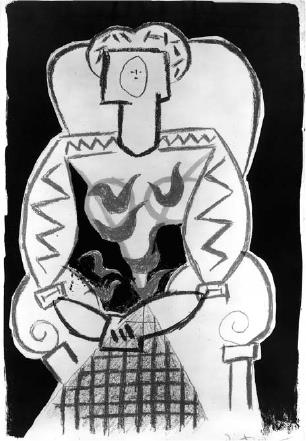

It’s impossible to characterize or classify the work of Spaniard Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) since his career as an artist spanned his entire life and he experimented with many disciplines. Picasso often claimed that he could draw before he could speak, and by all accounts he spent much of his childhood engaged in drawing. He was only 15 years old when he submitted his first works for exhibition. And by the turn of the century, when he was still a young man, he began exploring the blossoming modern art movement. The rest of his career breaks into several periods. His Blue period (1901–04) was named for the monochromatic use of the color for its subjects, and was likely the result of a despair brought on by the suicide of a friend. Next came his Rose period (beginning 1905), when images of harlequins and jesters appear in his works—all to a somewhat melancholic effect. He soon began to incorporate aspects of primitive art, and later experimented with geometric line and form in his works, which were constructions—or deconstructions—sometimes only identifiable by their title.

In the spring of 1912 cubism exploded, and Picasso was on its forefront. In 1923 he broke new ground with surrealism. The key masterpiece in his body of works came in 1937 when he painted Guernica, his rendering of the horror of the German attack (supported by Spanish fascists) on the small Basque town (of Guernica) in Spain. His career reached its height during the 1940s, during which he lived in Nazi-occupied Paris.

Biographer Pierre Cabbane summed up the last period (1944–73) of Picasso’s work: “He invented a second classicism: autobiographical classicism… His final 30 years were to be a dizzying, breakneck race toward creation.” During this time, Picasso did not chart any new artistic territory, but simply created art at an amazing rate. After his death in 1973, his estate yielded an inventory of 35,000 remaining works—paintings, drawings, sculptures, ceramics, prints, and woodcuts.

He left an enormous—even mind-boggling—legacy to the art world. In a 1991 article in Vanity Fair, Picasso’s friend and biographer John Richardson observed, “Almost every artist of any interest who’s worked in the last 50 years is indebted to Picasso … whether he’s reacting against him knowingly or is unwittingly influenced by him. Picasso sowed the seeds whose fruits we are continuing to reap.”