War and ConflictAfrica |

What happened in the Rwandan genocide? |

On April 6, 1994, the airplane carrying Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana (1937–1994), of Rwanda’s majority Hutu ethnic group, was shot down by unknown attackers. The event touched off, or was used as an excuse for, what one journalist described as a “premeditated orgy of killing” in which ethnic Hutu extremists carried out a campaign of mass murder against minority Tutsis. Ten years after the horrific events, the Chicago Tribune‘s Africa correspondent recounted how Rwanda’s “Hutu majority, equipped with machetes and called to action by government radio announcements, slaughtered neighbors, friends, co-workers. Priests killed parishioners who sought refuge in churches. Teachers murdered pupils. Hundreds of thousands of women were raped, children burned or drowned, bodies pushed into mass graves.” The massacre continued for three months, ending only when Tutsi fighters managed to seize the capital at Kigali and take power.

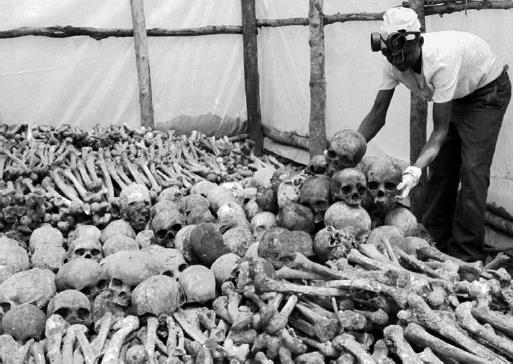

In 2004 the Rwandan government released its official estimate of the death toll: 937,000 people were murdered, making it the worst ethnic cleansing the world has seen since the Holocaust during World War II (1939–45). But, unlike the Holocaust, which was carried out by a dictatorial military machine, the Rwandan genocide was carried out by the masses. In the aftermath, more than 150,000 people were accused of participating in the massive violence, though the Rwandan courts had only tried a small fraction of those—no more than 10 percent in 10 years. An estimated 2 million Hutus, many who probably feared retribution, had fled to neighboring countries after the Tutsis gained power. The genocide had happened at the hands of many.

In the decade since the Rwandan genocide, Rwandans, and the world, have grappled with difficult and perhaps unanswerable questions. How could so many people (Hutus) have participated in the mass cleansing? Experts point to Rwanda’s deeply divided history; the rivalry between Hutus and Tutsis dates back hundreds of years—since the Tutsis first arrived in the central African region in the fourteenth century. How could the world body have “allowed” such an event to happen, particularly with the Nazi Holocaust a not-too-distant memory? Again, there is no easy answer. The United Nations withdrew its people when the violence began in April 1994, but some UN officials estimated later that perhaps as few as 5,000 troops might have been able to prevent the annihilation. The United States did not intervene in the Rwandan genocide; the recent images of dead American soldiers being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu, Somalia (in October 1993), had left the country reticent to involve itself in the world’s hotspots. But, even with the lesson of Rwanda, experts wondered how the international response might differ today. Finally, how can Rwanda rebuild? The governing Tutsis have been able to enforce a calm on the tiny landlocked nation. But some believe it is an uneasy calm and wonder how long minority Tutsis can retain control over a country that is 85 percent Hutu. In Rwanda’s efforts to serve justice, its jails and courts remained jammed 10 years after the genocide. And since so many had fled the country and others escaped prosecution, justice could not be served fully. Some legal experts thought that a general amnesty, issued by the Rwandan government, would help put the nation’s problems behind them.