Political and Social MovementsThe Civil Rights Movement |

What was the nonviolence movement? |

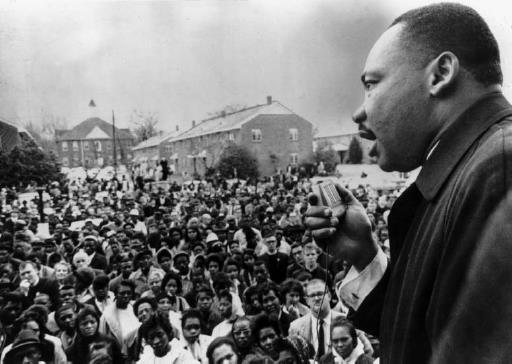

The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968) was committed to bringing about change by staging peaceful protests; he led a campaign of nonviolence as part of the civil rights movement. King rose to prominence as a leader during the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, when he delivered a speech that embodied his Christian beliefs and set the tone for the nonviolence movement, saying, “We are not here advocating violence…. The only weapon we have….is the weapon of protest.” Throughout his life, King staunchly adhered to these beliefs—even after terrorists bombed his family’s home. King’s “arsenal” of democratic protest included boycotts, marches, the words of his stirring speeches (comprising an impressive body of oratory), and sitins. With other African American ministers King established the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1957), which assumed a leadership role during the civil rights movement.

The nonviolent protest of black Americans proved a powerful weapon against segregation and discrimination: A massive demonstration in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 helped sway pubic opinion and motivate lawmakers in Washington to act when news coverage of the event showed peaceful protesters being subdued by policemen using dogs and heavy fire hoses. In response to the outcry over the event in Birmingham, President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) proposed civil rights legislation to Congress; the bill was passed in 1964. That same year Martin Luther King Jr. received the Nobel peace prize for his nonviolent activism.

King’s policy of peace was challenged two years later when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), tired of the violent response with which peaceful protesters were often met, urged activists to adopt a more decisive and aggressive stance and began promoting the slogan “Black Power.” The civil rights movement, having made critical strides, became fragmented, as leaders, including the highly influential Malcolm X (1925–1965), differed over how to effect change.

On April 4, 1968, King was in Memphis, Tennessee, to show his support for a strike of black sanitation workers when he was gunned down outside his hotel room shortly after 5:30 in the evening. As news of King’s death swept over the nation, blacks in 168 American cities and towns responded with rioting, setting fire to buildings, and looting white businesses. Commenting on the terror, radical African American leader Stokely Carmichael said, “When white America killed Dr. King last night, she declared war on us.” The chaos continued for a week: When the rioting ended on April 11, there were 46 dead (most of them black), 35,000 injured, and 20,000 jailed. Nevertheless, the violent crime that claimed the leader’s life and the violence that erupted after news spread of his death have not, decades later, overshadowed King’s legacy of peace and his message of the brotherhood of all people.