Economics and BusinessRobber Barons |

Who were the “robber barons”? |

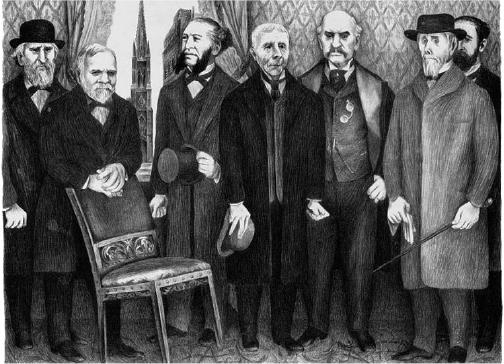

They were the industrial and financial tycoons of the late nineteenth century, the early builders of American business. Some called them the captains of industry. The “robber barons” included bankers J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) and Jay Cooke (1821–1905); oil industrialist John D. Rockefeller (1839–1937); steel mogul Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919); financiers James J. Hill (1838–1916), James Fisk (1834–1872), Edward Harriman (1848–1909), and Jay Gould (1836–1892); and rail magnates Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794–1877) and Collis Huntington (1821–1900). These influential businessmen were hailed for expanding and modernizing the capitalist system and lauded for their philanthropic contributions to the arts and education. But they were also viewed as opportunistic, exploitative, and unethical.

Many factors converged to make the robber baron possible. The new nation was rich in natural resources, including iron, coal, and oil; technological advances steadily improved manufacturing machinery and processes; the population growth, fed by an influx of immigrants, provided a steady workforce, often willing to work for a low wage; the government turned over the building and operation of the nation’s railways to private interests; and, adhering to the philosophy of laissez-faire (noninterference in the private sector), the government also provided a favorable environment in which to conduct business. Shrewd businessmen turned these factors to their advantage, amassing great empires. Reinvesting profits into their businesses, fortunes grew. The robber barons, especially the railroad men and the financiers who gained control of rail companies through stock buy-outs, hired lobbyists who worked on their behalf to gain the corporations subsidies, land grants, and even tax relief at both the federal and state levels.

The robber barons converted their business prowess into political might. In Washington, politicians grew tired of the advantage-seeking representatives of the nation’s business leaders. Reform-minded progressives complained that the robber barons lived in opulent luxury while their workers barely eked out a living, their families teetering on despair.

After dominating the American economy for decades, changes around the turn of the century worked to curb the influence of the robber barons. In 1890 the federal government passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, making trusts (combinations of firms or corporations formed to limit competition and monopolize a market) illegal; workers continued to organize in labor unions, with which corporations were increasingly compelled to negotiate; the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was established in 1887 to prevent abusive practices; and in 1913 the Sixteenth Amendment was ratified, allowing the federal government to collect a graduated income tax. Though many American businessmen and women would make great fortunes in the twentieth century, by the end of the 1920s the era of the robber barons had drawn to a close.