Classical Greek MythologyEuripides, Medea, and Dionysus |

What is the plot of Medea? |

Medea was first produced at the City Dionysia of 431 B.C.E. It takes up the story of the hero Jason and his sorceress wife after they return to Greece with the Golden Fleece, an ancient myth well known to Euripides’ audience. As with Sophocles, Euripides sought to extract a mythos, a viable plot for his play from within this long and complex story. The audience knew that in Corinth, where they lived after the Golden Fleece quest, Jason and Medea’s marriage had been threatened by Jason’s willingness to abandon his wife in order to make a politically advantageous marriage to Glauce, the daughter of the Corinthian king, Creon (not the same as Creon of Thebes in Sophocles’ Oedipus plays). The plot as developed by Euripides would focus not so much on Jason as on the inner turmoil of Medea, so, logically, the beginning—to use Aristotle’s formula—finds Medea grieving over her impossible position. She is a woman in a world dominated (like fifth-century B.C.E. Athens) by rules and traditions favorable to males, and she is an out-sider—a foreign, barbarian enchantress living in a Greek world. And her husband has deserted her. Even a Greek audience would have felt some pity, but the fear Aristotle said was necessary would have been generated by the audience’s knowledge of Medea’s powers, already demonstrated in the Golden Fleece aspect of the larger story.

In the middle of the plot, the agon, as Medea grieves and bemoans the horrors of her position, the king, Creon, arrives and, as does the audience, fearing Medea’s powers, announces that she is to go into exile. But Creon agrees to a one-day reprieve when Medea, pretending humility, requests it. At this point the audience, even more aware of Medea’s powers than is Creon, would have gasped at Creon’s willingness to allow what is, in effect, a time bomb, to remain in his territory even for one day.

Now a famous character, one well known to the Athenian audience, arrives. This is the legendary Athenian king Aegeus, the human father of the hero Theseus. Aegeus is swayed by Medea’s sad story and agrees to give her sanctuary in Athens if she can make her way there and if she will help his wife to conceive a child. Once again, knowing the story of Medea in Athens, and her attempt to rid the world of Theseus, the audience must have reacted in disbelief and horror. So far two powerful men have been somewhat out-maneuvered by Medea. The struggle between the protagonist Medea and the antagonist, the patriarchal world, proceeds, as Jason himself arrives. Jason attempts to justify his position, to explain rationally why it is best for him and the children, and even for Medea, to accept his new marriage. Furious, Medea accuses Jason of forgetting that she had left her home for him, that she had made his Golden Fleece quest a success, and that she was, after all, his wife. Jason leaves, and Medea plots revenge. She calls Jason back, apologizes, and pretends to have accepted the new marriage. She sends a poisoned robe to Glauce as a wedding present carried by her two children. Glauce and Creon are both killed by the poison.

The end comes when Jason enters as Medea has killed their children and is being taken away magically by a flying chariot.

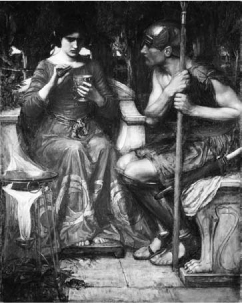

The hero Jason and his sorceress wife, Medea, shown here in a 1907 painting by John William Waterhouse, are the subject of a play by Euripides.