American PhilosophySocial Darwinism |

Did all nineteenth-century thinkers believe in progress? |

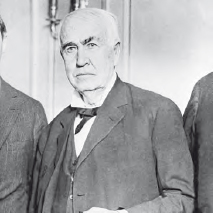

Thomas Edison (1847–1931) certainly did. In 1876, when he set up his laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, he committed himself to “a minor invention every ten days and a big thing every six months or so.” (Edison did get about 40 patents a year and over 1,000 before he died.)

Not everyone was so enthusiastic about new machines, though. Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), for example, wrote in 1829 in “Signs of the Times,” an essay that was published in the Edinburgh Review. (the signs being “The Age of Machinery”) that “the shadow we have wantonly evoked stands terrible before us and will not depart at our bidding.” Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) wrote in Walden (1854): “We do not ride upon the railroad; it rides upon us.”

Still, many did share Edison’s optimism, and it was the popular national view. Timothy Walker, a lawyer from Ohio, wrote in the North American Review in 1831 that machines free ordinary people from burdensome labor and promote democracy.