New PhilosophyJacques Derrida and Deconstructionism |

How did Derrida explain deconstructionism in his Of Grammatology? |

Derrida’s Of Grammatology (1972) is about the instability of texts, due to the fact that all writing depends on the meanings readers bring to it, which may change, so that it cannot be claimed that a given piece of writing has a specific and stable meaning. All signs depend on other signs for their meanings, so there is never an ultimate meaning—meaning is always “deferred.”

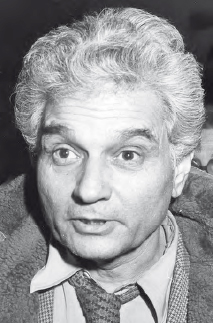

Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) speaks of “arche-writing” in this regard, which refers to gaps in the meaning of what is sacrosanct. All writing is split between its intention and how a reader understands it, and there is a gap between the writer and the reader.

Derrida’s description of the reality of writing is meant to be an accurate account of the nature of intellectual life. The imagined presence of a being before whom the intentions and meaning of the philosopher is grasped, is the illusion under which philosophers and others have labored for so long.

Derrida thought that there was an ambiguity in the spoken word, which made the written word necessary, and he introduced the term “differance” to write about this difference. If one says “differance” and “difference” aloud there is no audible difference between them. The relevant difference can only be expressed in writing, although we have already seen how meanings are inconclusive in writing.

It is this insight about the dynamic nature of meaning—against Ferdinand de Saussure’s (1857–1913) structuralist view that there is a system of meaning constituted by speech, for which the written word is somewhat secondary, if not unnecessary—that earned Derrida the label “poststructuralist,” beginning in 1968. Derrida criticized the structuralist tradition as “moving from center to center in futility.”