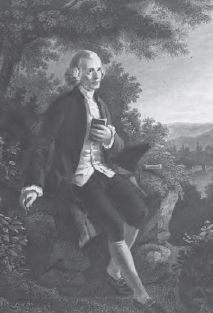

The Enlightenment PeriodJean-Jacques Rousseau |

What was Rousseau’s life like? |

Rousseau’s life seemed to spin out of control from time to time, although he found a degree of stability, intellectually, in his writing. He was born in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1712 and always considered himself a citizen of that canton (city-state). His mother died nine days after his birth. His father, an unsuccessful watchmaker, and his aunt raised him. His father was an emotional man, often reading sentimental novels and Plutarch.

As a boy, he was subjected to abuse outside the family. In his Confessions, Rousseau described the erotic effect of corporal punishment from a pastor’s sister. Later, a notary and an engraver, to whom he was apprenticed, abused him. Rousseau left Geneva at the age of 16, and soon met Françoise-Louise de Warens, a Catholic noblewoman who became his lover and motivated him to convert to Catholicism.

In 1742, he went to Paris to present a new system of musical notation to the Académie des Sciences, but his system was rejected. He then became secretary to the French ambassador in Venice, Italy, in 1743, but left within a year after quarrelling with him. Back in Paris, he began a lifelong relationship with a seamstress named Thérèse Levasseur. He met Denis Diderot (1713–1784) and began contributing articles on music to his encyclopedia. He then submitted an essay for a competition at the Academy of Dijon in answer to the question of whether the arts and sciences had benefited mankind. Rousseau’s resounding negative answer was Discourse on the Arts and Sciences (1750). It won and made him famous. His opera Le Devin du Village was much appreciated by King Louis XV, but Rousseau did not get a pension from him because he immediately supported Italian over French music.

Rousseau then returned to Geneva and converted back to Calvinism. He wrote The Discourse on Inequality in 1755, which caused an alienation from Diderot and other patrons, because it claimed that most human inequalities were the result of society, not nature; Rousseau believed man was born good. But he secured the support of the very rich Duke de Luxembourg. His romantic novel Julie; ou la nouvelle Héloise was a big success and was followed by Of the Social Contract (1762; also known as Principles of Political Right), and Émile; or, On Education (1762). All of these writings were critical of established religion and therefore banned in both France and the canton or city-state of Geneva. Rousseau fled arrest in 1762 (brought on by the uproar about his political ideas), and after some disorganized travels, finally, in 1765, prevailed on the hospitality of the very English David Hume (1711–1776). The latter situation did not work out, however.

Rousseau reentered France in 1770 under the assumed name “Renou,” and went to Paris. He had begun work on the Confessions, in England, but the completed edition was not published until after his death. He wrote Considerations on the Government of Poland after an invitation to make recommendations for a constitution for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This was followed by his Dialouges: Rousseau (1776, published in 1782), Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1782), and Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1782). He then wrote an analysis of Gluck’s opera Alceste, before dying suddenly in 1778.