Confucianism, the Literati, and Chinese Imperial TraditionsSigns and Symbols |

Is there such a thing as Confucian art? |

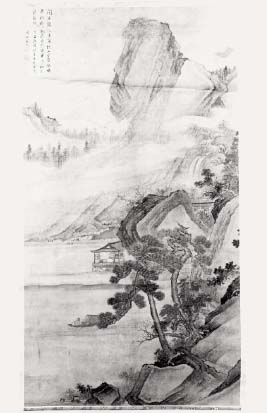

A number of Confucian Literati have been credited with some of China’s finest landscape paintings. They were particularly attracted to this artistic theme and medium because both were consistent with deep-rooted Confucian values. Images of mystic mountain settings shared scroll space with equally haunting poems that reflected on human life and the grandeur of nature. These visual and literary images were sometimes autobiographical in tone, offering insight into the creator’s personal spiritual convictions. Paintings often depicted solitary scholars lost in contemplation of natural beauty, meditating on moon-rise or creating calligraphy in a mountain pavilion. Here Confucian tradition crosses paths with classic Daoist views of nature and with the spontaneous and abstract landscapes painted by Chan Buddhist monks. Painting and poetry became forms of meditation for the Literati, expressions of their holistic view of the balance and harmony of nature. Literati painting is a didactic art with ethical impact, for ideally it expresses the feelings of the superior person. Confucian theory accords visual art the ability to communicate ideas too delicate or too forceful for words. The mind of the artist takes precedence over the content of the work, for the ultimate benefit of a great work is that it offers a connection with a person who represents the highest moral values. Great art can arise only out of genuine virtue.

An example of a Literati landscape, this meditative hanging scroll painting called “Pavilion in a Landscape” (dated 1757) shows the classic “mountain-water” imagery influenced by a Daoist worldview, with nature dominating and signs of human life and habitation blending in. (The Saint Louis Art Museum.)