Confucianism, the Literati, and Chinese Imperial TraditionsReligious Beliefs |

What do Confucians believe about ultimate spiritual reality? |

Two of the most important concepts that define what Confucius and his followers thought about ultimate spiritual reality are the Dao and Heaven (tian). Confucian texts do not always make clear how the two differ, and at times it seems they are virtually interchangeable. In Confucian teaching, the Dao and Heaven are generally nonpersonal realities that are equivalent, respectively, to a primordial or eternal cosmic law (Dao) and the source of that law (Heaven). Early Confucian texts emphasize the immanent, rather than the transcendent, aspect of the Dao. For example, Confucius is reported to have observed that the Dao is very close to human beings. Dao is therefore accessible and knowable, but that does not mean the Dao is not also mysterious. Confucius did not simply deny the existence of transcendent realities. He preferred to interpret ultimate reality from the ground up, so to speak.

Many of history’s great theologians have constructed their systems of thought by beginning with the existence of some divine reality and working their way down. Not Confucius. He was interested primarily in the ethical implications of traditional teachings that he had inherited. He apparently thought of Heaven as the ultimate moral authority or principle. Heaven makes its “will” known to, and through, an upright sovereign. What Heaven discloses is, in turn, the Dao. Confucius reportedly described “his” Dao as consisting of two fundamental ethical components, responsibility or loyalty (jung) and reciprocity (shu). His interpretation of Dao and Heaven is therefore quite different from the traditional Daoist interpretation. In much of Daoist thought, Dao has priority and gives rise to Heaven, which in turn manifests the “ten thousand things” that many people call creation or the universe.

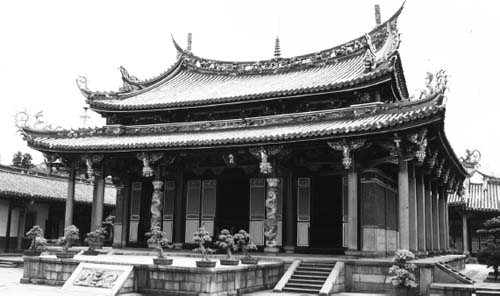

Main memorial hall of Taipei Confucius temple. Note the dragon columns on the porch and dragon design on the front pedestal.