The Rehnquist Court (1986–2005)Miscellaneous |

Do detained “enemy combatants” have constitutional rights and access to the U.S. court system? |

Yes, they have some rights with regard access to courts, although the exact nature of their rights has yet to be determined. Most recently, the Roberts Court ruled in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006) that certain military commissions created by President George W. Bush were unconstitutional. However, the Court’s opinion still did not explain the exact level of constitutional rights for the detainees. It will likely take more decisions from the Roberts Court to settle these divisive issues.

In the War on Terror, which began during the Rehnquist Court, following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the American government declared hostile individuals fighting U.S. and allied forces in Afghanistan and Iraq as “enemy combatants.” This designation carries legal significance because persons classified as “prisoners of war” receive the protection of the Geneva Convention. Enemy combatants do not receive the full protection of the Bill of Rights, as do regular criminal defendants. Instead, the U.S. government argued that individuals classified as enemy combatants had virtually no rights at all.

The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed in a pair of decisions—Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (2004) and Rasul v. Bush (2004).

In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, the Court ruled 6–3 that an American citizen fighting for the Taliban against the United States did have a right to contest the factual basis of his confinement before some sort of neutral decisionmaker. “A state of war is not a blank check when it comes to the rights of the Nation’s citizens,” wrote Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. She added that “history and common sense teach us that an unchecked system of detention carries the potential to become a means for oppression and abuse of others.”

However, the Court did find in the government’s favor on the threshold question of whether the executive branch could detain persons identified as “enemy combatants.” On this question, Justice O’Connor reasoned that the executive branch had this power because the U.S. Congress authorized it in a resolution called “Authorization for Use of Military Force.”

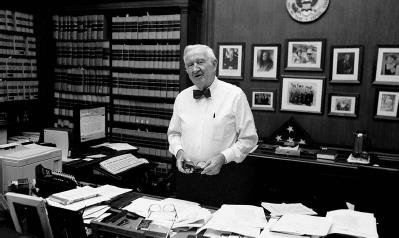

In Rasul v. Bush, the Court ruled 6–3 that even noncitizen detainees at Guantanamo Bay have the right to access U.S. courts to challenge their confinement in a federal habeas corpus proceeding. However, the Court did not explain exactly what procedure was due the detainees. Justice John Paul Stevens explained in his opinion that the question before the court was “only whether the federal courts have jurisdiction to determine the legality of the Executive’s potentially indefinite detention of individuals who claim to be wholly innocent of wrongdoing.”