The Marshall Court (1801–35)Decisions |

In what famous decision did Marshall broadly define Congress’s interstate commerce powers? |

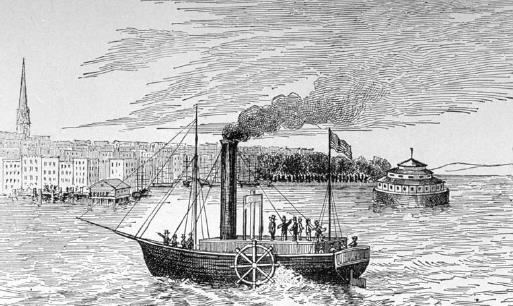

The Marshall Court broadly defined commerce in its 1824 decision in Gibbons v. Ogden in a battle of steamboat entrepreneurs. The state of New York granted an exclusive license to Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton, the inventor of the steamboat, to operate steamboats in the New York Harbor and the Hudson River. Livingston and Fulton then licensed Aaron Ogden to operate steamboats from New York City to Elizabethtown, New Jersey.

Ogden’s former business partner, Thomas Gibbons, wanted to break up this monopoly. He had acquired a federal permit to operate steamboats between New York and New Jersey. Gibbons contended that because he had a federal permit, he did not need to obtain permission from the state of New York. Ogden sued Gibbons, arguing that Gibbons’s activities were infringing on Ogden’s exclusive monopoly from the state of New York. Ogden sought an injunction, ordering Gibbons to cease infringing on his exclusive privilege.

Gibbons, backed by the wealthy Cornelius Vanderbilt, fought back in court by hiring perhaps the best lawyer in America—Daniel Webster. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Ogden’s exclusive monopoly was invalid because it infringed on Congress’s Commerce Clause powers. Marshall broadly defined the powers of Congress’s commerce powers, writing: “Commerce, undoubtedly, is traffic, but it is something more: it is intercourse. It describes the commercial intercourse between nations, and parts of nations, in all its branches, and is regulated by prescribing rules for carrying on that intercourse.” The decision was important because it was an example of the U.S. Supreme Court broadly defining Congress’s Commerce Clause powers.