Chapter Two

So What Does Open Mean?

Andrew Ng is an Associate Professor, and Director of the Artificial Intelligence Lab at Stanford University in California. He’s an engaging presenter, so it’s not surprising that his courses are some of the most popular on campus. Machine Learning (‘the science of getting computers to act without being explicitly programmed’) attracts about 350 students per year. But when Andrew decided to open the course to the general public, over 100,000 people registered. Coursera administers Machine Learning, and a growing range of online courses, to students around the world.

Although a for-profit start-up, Coursera has, at the time of writing, offered its courses for free in its first two years of existence, and over 4.5 million students have already signed up. ‘Classes’ are typically 8-10 minute video lectures, interspersed with short quizzes, to test for comprehension. There are also question and answer forums, with an astonishing average response time of 22 minutes. This is attributed to having students scattered around the world – there is almost always someone online, 24 hours a day, willing to offer a response. With such large numbers, having academics assess student work became unrealistic, so Coursera instigated peer assessment. Tens of thousands of students graded each other’s work. Many academics were horrified at the prospect of students assessing each other, but pilot studies demonstrated that peer grading at Coursera almost always correlates to tutor grading.

Daphne Koller, Coursera’s co-founder, is convinced that Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) such as Machine Learning have the potential to ‘establish education as a fundamental human right, where anyone around the world with the ability and the motivation could get the skills that they need to make a better life for themselves’.

A farmer in a remote village in Africa finds his small potato crop under attack from ants. He cycles to the cyber cafe in the nearest town and learns that the ants are repelled by scattering ashes on the soil around the potatoes. On returning home, he scribbles down the solution, and pins it to the village noticeboard so that his neighbours can follow suit. A whole village escapes a devastating drop in collective income. Colonies of ants have to look elsewhere for food.

In pubs all over England, small groups of people who share a passion for beer and philosophy gather to discuss modern-day dilemmas such as ‘Can the use of power ever be justified?’, ‘What is the purpose of literature?’ and ‘Is “Why” a daft question?’. The ‘Philosophy in Pubs’ group may wish to plan a vacation to Seattle to meet the ‘Drunken Philosophers’, or indeed (for somewhere warmer) to Singapore where 25 members regularly meet at the Raffles Hotel. There are groups of amateur philosophers meeting in cafes and pubs in almost every major city around the world. Nothing new in that – philosophers have been doing it for centuries. But now they are no longer intellectual cliques, they’re open to anyone.

It’s not just philosophy. Anyone who wants to meet people and learn something new simply has to go to the meetup.com website, where every possible (legal) interest is catered for. Meetup enables over eight million users, in over 100 countries, to physically attend over 50,000 Meetups per week. Yes, you read that right – per week. Its founder, Scott Heiferman, had the idea of a global noticeboard, in the wake of 9/11 and, specifically, after reading Robert Putnam’s account of an increasingly disconnected America, ‘Bowling Alone’. Like many social entrepreneurs, he is passionate about harnessing global communications to build stronger local communities.

These examples are a fairly random, microscopic slice of a phenomenon which is radically re-shaping how we live, work and learn in the 21st century. You probably take part in a revolutionary act several times a day. It may not feel very revolutionary, partly because we’re in the thick of it, without the benefit of hindsight and partly because in a relatively short space of time it has become almost second nature for us to learn differently.

‘Open’ is a disruptive force because in the places where we spend most of our waking hours – the office, school or college – it’s been pretty much business as usual. It’s often said that a time-traveller from the 19th century, beamed into today’s world, would be bewildered by everything he witnessed, but would instantly feel comfortable in a school. Similarly, although the tools of the trade have changed, today’s office learning culture has changed little since the 1960s.

Now, these two sectors are coming under intense pressure to radically overhaul their learning systems. The problem stems from the ways in which we learn when we have a say in the matter. We’re becoming increasingly dissatisfied, and consequently disengaged, from the way we learn in the formal space, when measured against the open learning we do in the social space. It’s why North London rapper, Suli Breaks says, in his viral video of 2013, that he ‘loves education, but hates school’ and why workers avoid office-based training programmes, but eagerly take part in weekly Twitter discussions with colleagues around the world.

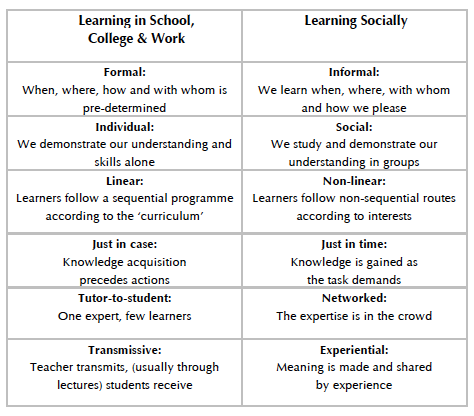

It’s too easy to characterise those contrasting experiences in terms of the presence, or absence, of technology: mobile phones being confiscated in school; Facebook banned in the workplace. I believe that it’s more complicated, and much more exciting, than that. The cause of our dissatisfaction lies not in being denied access to software or hardware but in being denied access to different ways of learning and different people to learn from. It turns out that our preferences for how we learn in the social space are the polar opposites from those enforced by our institutions:

(Click to enlarge this table)

I’m not suggesting that all the learning taking place in businesses and schools is defined by the list in the left-hand column. Nor is social learning defined by all of the qualities on the right. But enough of it is to warrant a radical reappraisal of how we do things.

Open learning is frequently, and in my view, incorrectly trivialised as people ‘just chatting’ on social media. My belief is that this perception misses the point: ‘open’ is not simply about technology, it’s about behaviour shift as well.

In the 1980s, the proliferation of what became known as ‘e-learning’ saw our learning institutions take traditional face-to-face methods of teaching and learning, and digitise them. The promise it offered was only matched by our sense of disappointment in what materialised, as the novelty of switching on a computer replaced attending a lecture, and words on a screen replaced words on a page. E-learning in colleges and universities suffered the same fate as the ‘interactive whiteboard’ in schools: a quick hop from ‘this changes everything’ to ‘well, that didn’t work’. Digital technologies will no more solve the so-called ‘crisis in education’ than airbags will stop drivers from having accidents.

What digital technologies can do, however, is to dramatically accelerate the changes in behaviours, values, and actions, which then transform the way we learn and our capacity to learn. Most people working in learning have experienced one of those light-bulb moments when they realise the enormity of the change that is upon us. Mine was when I realised formal education could no longer look upon learning which happens socially as either inferior or complementary. Rather, it’s a direct challenge to centuries-old orthodoxies, and simply can’t be ignored. The light bulb went off in an unlikely, and unexpected, place.

In 2005, I took both my then adolescent sons to the WOMAD Festival of World Music in Rivermead, England. Since it was the first time either of them had heard many of the musical styles being showcased that weekend, I was curious to see which of them would grab their interest. It turned out that the band which had the biggest impact on my eldest son, Jack, was a group of Tuvan throat singers, called Huun-Huur-Tu. Tuva is one of the remotest parts of Russia, bordering on Outer Mongolia, and throat singing creates some of the most extraordinary sounds you’re ever likely to hear. The technique is often called ‘overtone’ singing, because the voice manages to create several pitches at once. To western ears, where we were reasonably satisfied with just the one pitch at a time, it sounds both magical and, because the overtones come from deep in the throat and have to be forced out, quite painful.

Like many traditional forms of music, it’s a lot more complex than it first appears. Conventional Tuvan wisdom has it that you would need to spend years of apprenticeship with an acknowledged master singing, gradually exploring hitherto inaccessible regions of the larynx and vestibular folds, before you could produce overtones. And there’s not just one technique. A quick dip into Wikipedia reveals that ‘the three basic styles are khoomei, kargyraa and sygyt, while the sub-styles include borbangnadyr, chylandyk, dumchuktaar, ezengileer and kanzyp. In another, there are five basic styles: khoomei, sygyt, kargyraa, borbangnadyr and ezengileer. The sub-styles include chylandyk, despeng borbang, opei khoomei, buga khoomei, kanzyp, khovu kargyraazy, kozhagar kargyraazy, dag kargyraazy, Oidupaa kargyraazy, uyangylaar, damyraktaar, kishteer, serlennedyr and byrlannadyr‘. (Top tip: don’t ever try to beat a Tuvan at Scrabble.)

So, imagine my astonishment when, a mere six weeks after the WOMAD festival, Jack asked me if I’d like to hear his kargyraa. “Sure,” I replied, pretending I knew what he was talking about. He then produced a deep growling sound which, gradually, layered a sweet, melodic, whistle-like overtone on top. I could not have been more astonished. I knew that he’d not undertaken any trips to Mongolia in the previous six weeks. Nor, to the best of my knowledge, was he proficient in herding horses. How, I asked, had he managed to acquire a skill that takes years of mentored study? “Oh, some English bloke spent a few years over there, and stuck a bunch of free modules up on the net. I just taught myself by following them.”

This was my introduction to the open learning phenomenon that is sweeping the globe. From years of face-to-face apprenticeship, to just a few weeks of online study. And in 2005, this phenomenon had barely started. If Jack wanted to further extend his Tuvan repertoire (though I think his interest probably waned once the novelty of being able to do something totally unexpected wore off), all he’d have to do is to Google ‘Tuvan throat singing’, and he’d have 1.5 million avenues to explore: YouTube tutorial videos by the hundred; overtone singing forums by the score; a regular Tuvan Throat evening in a pub in Darwen, Lancashire; someone in Australia looking for an online coach; and, of course, the inevitable Facebook Tuvan Throat Singing page. Don’t take my word for it. Google it yourself.

Fortunately, there aren’t any actual Throat Singing Schools in northern England. Because if there were, they’d have to be finding a new business model. ‘Open’ is fundamentally challenging teachers of just about everything.

One of the reasons behind MOOCs popularity in the US is that public investment now demands a better return, particularly in student achievement. It’s not widely known, but of the 18 developed nations participating in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) assessments, the US comes bottom on college graduation rates. There’s considerable room for improvement.

For example, in 2011, four-year graduation rates for the San Jose State University (SJSU) were just seven percent; fewer than 50 percent of their students graduated after six years. Despite these appallingly low statistics, SJSU sits mid-table in the national public university rankings. As performance indicators go, we’re in a sea of low expectations.

The Governor of California, Jerry Brown, decided something had to be done. In January 2013, he announced plans to pilot remedial online courses, delivered by Coursera’s rival, Udacity, at SJSU. Governor Brown was no doubt emboldened by a review of research, undertaken by the US Department of Education, which concluded that ‘students who took all or part of their class online performed better, on average, than those taking the same course through traditional face-to-face instruction’.6 If the pilot programme succeeds, open online learning is likely to be introduced in all Californian universities, and when it comes to education, what California does today, the rest of America does tomorrow.

Arthur C. Clarke famously said that “Teachers who can be replaced by a machine, should be”. David Thornburg reworded it to “Any teacher that can be replaced by a computer, deserves to be”. Around the world that replacement process is starting to happen, as more courses go online, and more video tutorials are uploaded. As the evidence accumulates that online learning at worst does no harm and at best out-performs face-to-face, more learning institutions and teachers will have to ‘blend’ their teaching. We will see more alternatives to lectures in large halls, via anytime, anywhere online viewings. But it isn’t simply the when and where of learning that’s being transformed – it’s the how, too.

Back To the Future

The aspect of ‘open’ that is the most thrilling is the nexus of old and new. Put simply, the incredible tools we now have at our disposal are bringing us back to ways of learning that had long been discredited. To fully explain this, I need to give a potted history of how learning is organised. As we don’t have the space, it will be necessarily simplistic, I’m afraid, but you’ll get the point.

As far back as the Ancient Greeks, educators have disagreed about how people learn best. The historian Plutarch’s quote that ‘The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled’, neatly encapsulates two opposing views. Those who advocate ‘didactic’ instruction put the teacher at the centre: the best way to learn is for the expert to transmit and the student to receive, pouring knowledge into an empty vessel. Retaining this knowledge has always been a bit of a challenge, so rote learning – memorising and reciting facts, multiplication tables, and so on – usually accompanied didactic/transmissive teaching.

As Sir Ken Robinson has brilliantly observed7 this method of instruction8 was easy to measure – didactic teaching begat rote learning, which in turn begat paper-based examination. It became the dominant method of learning in universities, neatly side-stepping the tiresome reality that in real life we’re usually tested by our competence in performing tasks. Since we tend to only value what can be measured, that’s the way it’s stayed, until almost the present day.

The main vehicle for this form of learning is ‘the lecture’ and the main tool for rote learning became note taking. Once schools became universal they fashioned themselves after universities. I vividly remember endless ‘lessons’ in my secondary school that consisted of the teacher copying extracts from textbooks on to the chalkboard. We were then instructed to copy this into our notebooks. It was never explained why we had to do this – I can only presume that writing down what was already available in print was believed to assist memory. Clearly, little had changed since Mark Twain observed that ‘College is a place where a professor’s lecture notes go straight to the student’s lecture notes without passing through the brains of either’.

There have, however, always been advocates of more ‘experiential’ or ‘active’ forms of learning, where the student assumes the central role. John Dewey, Jean Piaget, Maria Montessori and Rudolph Steiner argued that the learner wasn’t an empty vessel, but carried experiences and knowledge that should be progressively built upon with the learner’s full and active involvement. With these approaches – broadly labelled ‘constructivist’ – it’s the tutor’s job to ‘scaffold’ experiences so that the learner can make connections, build confidence, reinforce skills, and apply knowledge to solve problems.

There have been some high-profile products of these so-called ‘progressive’ learning systems. For example, the founders of two of the most successful companies in the world – Amazon (Jeff Bezos) and Google (Larry Page and Sergey Brin) all attended Montessori schools. Larry Page credits going to Montessori, not Stanford University, as the reason for his success:

“I think it was part of that training of not following rules and orders, and being self-motivated, questioning what’s going on in the world, doing things a little bit differently.”9

Despite notable alumni, advocates of constructivist teaching have been outnumbered by those calling for more traditional methods for perhaps a decade or more, at least in the UK and the US. Striving to achieve a high ranking in international comparison tables, like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), has fostered a desire to get ‘back to basics’. Using high-stakes accountability to improve basic literacy and numeracy skills has been the focus of those countries attentions.

While the popular debate on how best to teach continues to swing back and forth, its anchor point – the centrality of school as an institution – has changed remarkably little over the past 150 years. For even the biggest critics of compulsory schooling it was hard to see how else we could educate young people. Even though I didn’t enjoy my school career, pretty much the only alternative to going to school, during 1970s England, was to be home-schooled – and this was virtually unheard of among working-class families. The only other place you could acquire knowledge was in local libraries, but they were as boring as school.

The Inexorable Rise of The Informal

‘Open’ is shifting the focus of attention from how we should teach, to the best ways to learn. It’s no longer about traditional vs progressive, didactic vs experiential. Instead, it’s about what we can do for ourselves, how we can tap into the knowledge and expertise that is within all of us, but rarely mined. In short, it’s about the rise of informal learning.

Informal opportunities to gain wisdom and practice new skills have mushroomed exponentially, and this alters not just how we see knowledge, but how we see the power relationships behind that knowledge. The hierarchy between teacher and students is being transformed through open learning – from vertically downward (expert to novice) to horizontally networked (participant as expert and learner). Arising out of a number of behaviour shifts: the desire for informality; the uncovering of layperson expertise; and a loss of deference for ‘experts’, we are finally witnessing the transformation of learning. It has to be said that some teachers and academics are appalled by these shifts. It’s hard to appreciate the significance of the loss of deference, and the attendant rise of informality, because they’ve crept up on us gradually over the past thirty years or so. Back then, our definition of ‘informal’ used to be very different.

I was a mature student in the early 80s. Having never believed I was bookish in any way, I was pleasantly surprised to get a first-class degree and for a while toyed with the idea of an academic career. Having applied for a PhD studentship there, I was invited to attend an ‘informal’ interview at the Open University in England. The panel consisted of thirty or so of the leading cultural theorists in the UK at the time. The 25 minutes that the interview took were so horrendous I have blanked them out of my memory, but the thing I will never, ever forget, was the point at which I was asked if I had any questions for the panel. Suppressing the urge to ask the real questions that were racing through my head (“Where’s the exit?”, “Could someone just shoot me now?”) I asked if it would be possible, during my PhD studentship, to sit in on some lectures. Cue much sniggering, and then finally one of the professors loftily declaimed, “We don’t give lectures, we just write books!”

Oh, how they all laughed.

I’m sharing this anecdote, not as therapy (though I do feel much better now, thank you) but because it illustrates our changing attitudes towards authority and informality. If those professors are still working at the Open University, they will not only be much more accountable, but they will have witnessed a redefinition of ‘open’. The Open University is, thankfully, now making its resources available to anyone, and, in 2013, even launched a collaborative learning initiative: Social Learn.10

While there are some educators who see the rise of informality as a sure sign that we’re all going to hell in a handcart, for many, shedding the responsibility of being expert-in-everything is not only liberating, it’s radically changing the way they work. Encouraging learners to share what they know, and constructing knowledge together, subtly shifts our expectation of teachers and other leaders of learning: from giving authoritative answers to asking challenging questions; from the sage on the stage, to the guide on the side.

The best learning professionals appreciate the complexity of the dramatic changes we’re witnessing, and the implications for how we structure teaching and learning. Advancements in what we now know, in technology, neuroscience, emotional intelligence, self-perception, and much more, are making thoughtful practitioners fundamentally re-evaluate their work. The imperative now is not to incrementally improve traditional models, but to rethink everything, to make it ‘open’.

The public debate, however, ignores this complexity for a more reassuring simplicity, encapsulated in Ken Robinson’s lament: ‘we keep trying to build a better steam engine’. Whenever education is discussed in the media, politicians and parents alike inevitably retreat into a ‘when I was at school’ certainty, based upon little more than a nostalgic belief that, if it worked for them, it should work for everyone. They are apparently oblivious to the challenge to formal education that the rise of the informal presents.

Why, for example, should the end-users of formal education – students – be satisfied with attending a physical centre five days a week, using technology that, in many schools, is slower and more restrictive than the tablet or mobile phone that they carry with them (but are usually prevented from using) when in school? Why should we continue to group young people by the year they were born, to study subjects copied from 19th-century universities, when their passion outside school is to develop skills, learning alongside people of all ages, effectively organising their own ‘curriculum’?

Open For Business

While the political pendulum swings between more traditional and progressive approaches to teaching and learning, there has been rather more consistency in learning at work. And it turns out that, without the political intervention we see in formal education, we view approaches to learning as less of a battle between the didactic and experiential, and more of a blend.

We have had forms of apprenticeship, for example, since the Middle Ages. Raw novices acquired skills by observing and mimicking master craftsmen over an extended period of time. Indeed, acceptance as a craftsman was to be labelled ‘time-served’. Apprenticeships were overseen by unions and tradesmen’s guilds and worked very effectively until the loss of heavy industry in the West and the accompanying decline in trade unionism.

The white-collar equivalent of apprenticeship is the internship. Internships have become quite controversial in recent years. At its best, an internship is the route to a permanent job. At its most cynical, an internship ensures a university graduate is paid little or not paid at all, given little or no training, and has little prospect of a job at the end of the period of internship.

Notwithstanding, the potential for low-wage exploitation, internships and apprenticeships are generally favoured by employers because they are classic examples of the value of learning by doing. Young people tolerate internships because it’s becoming increasingly difficult to go straight from higher or further education to a job, without something in between.

As we’ve seen, the global drive to lower production costs has fuelled the growth of knowledge process outsourcing. This means we’re not only seeing jobs disappear, but with them, the learning capital of an organisation. If a business is simply buying in knowledge, as and when it’s needed, how is it going to grow its own bank of knowledge and expertise?

Learning at work is, in fact, currently facing a kind of perfect storm: increasing business complexity; a growth in knowledge process outsourcing; consistently lowered production costs and a revolving door of employees and interns – all ratcheting up pressure on CEOs and company functions such as learning and development for quick fixes. To cap it all, the rise of open learning is now causing some CEOs to wonder whether there is any point in trying to nurture organisational learning at all.

What’s known as ‘open source learning’ – where networked learners collaborate to improve practices, prototypes and models – is making innovation happen far quicker than a company’s research and development department can manage. As a result, some major corporations have begun to look outside the organisation for innovation (more of this in the next chapter).

But they are in a minority. Most companies still see learning and development as a synonym for ‘training’ rather than innovation. Indeed, one of the indicators of the weather-vane nature of learning in the workplace is the uncertainty of where it fits into the organisational chart. Is it a function of research and development? Human resources, perhaps? Or should it be Knowledge Management? Or, as is the case with some enlightened companies, is learning everyone’s responsibility?

Wherever it is located, our understanding of how employees learn best has undergone significant revision during the past thirty years or so. Aside from some maverick organisations, the predominant pattern has always been that knowledge travels downwards: from senior executives, to more lowly staff, via training materials and courses. Sometime around the mid-1990s we began to understand that knowledge could be found anywhere within a company, but that it needed to be coordinated. Enter Knowledge Management. Knowledge Management became fashionable around the millennium, though it has consistently struggled to accurately define itself. That struggle continues, because with open learning, the very idea of managing knowledge becomes almost contradictory.

We are slowly understanding that learning in the workplace has to travel upwards, as well as down. And to ensure that learning flows in both directions, we have to work with a complex set of factors: human behaviour, supportive technologies, workplace cultures, personal motivation, employee engagement, to name but five.

The Informal At Work

A classic case of trying to stimulate knowledge growth is Xerox’s Eureka Project. In the early 1990s Xerox’s 20,000 customer service engineers were becoming more mobile, with more of them working on the road. As a result, technical know-how was becoming locked within individuals. By observing technicians on call-out it became apparent that when an engineer found a problem for which the manual had no answer, they contacted a colleague on a two-way radio.

The more unusual solutions were usually retold, and elaborated upon, at co-worker meetings. It was here that the Eureka moment arrived. Daniel Bobrow and Jack Whalen, of the Palo Alto Research Center, led a radical experiment in knowledge sharing: “It suggested to us that we could stand the artificial intelligence approach on its head, so to speak; the work community itself could become the expert system, and ideas could flow up from the people engaged in work on the organization’s frontlines.”11

Piloting the Eureka Project in France, customer service engineers were invited to submit tips through forum-based software. Few of Xerox’s managers believed that there was any value to be gained from worker-produced tips and tricks. But the engineers – after some initial resistance – saw the benefits.

Gradually, the resource bank of solutions grew. Assuming that sharing professional secrets would need extrinsic motivation, Xerox initially offered CSEs a $25 incentive for uploading a tip on to the Eureka database. The workers rejected the offer. As one said, ‘‘this would make us focus on counting the number of tips created, rather than on improving the quality of the database.’’ The incentive to contribute was simpler: workers simply wanted recognition, by having their name attributed to popular tips. By the time Eureka was rolled out across all Xerox countries in 2001, over 50,000 worker tips had been added to the database. Having now become a seminal example of a ‘community of practice’ the Xerox model has since been widely copied (pun intended).

The Eureka Project has become the stuff of legend in organisational learning because it was one of the earliest documented cases of the power of informal learning, shared and grown by the employees, not management.

The rise of the informal means that learning becomes harder to pin down, harder to manage. Michael Polyani was one of the early pioneers of informal learning. Until Polyani’s emergence in the 1950s, few had challenged the dominance of what was known as the ‘scientific method’ of learning. This method is familiar to all scientists and relies upon a sequenced operation: asking a question; forming a hypothesis; testing and analysing; replicating under controlled conditions; being reviewed by peers. It is as objective a process for gaining new knowledge as we have yet imagined. In medical research it has led to many breakthroughs, while also keeping patients safe.

Polyani, however, argued that when it comes to learning, true objectivity is impossible, since all acts of discovery are personal and fuelled by strong motivations and commitments.

Rather than being disappointed by the inevitable introduction of feelings, Polyani argued that we should welcome human passions in the workplace, since they lead to imagining, intuition and creativity. His belief that ‘we can know more than we can tell’ led to the emergence of ‘tacit learning’: we learn, not simply by logical reasoning, but by observing, absorbing, tinkering, following hunches. Tacit knowledge may be hard to define but there’s no doubting its existence. Think about how you recognise a person’s face. Now, try to explain it. That’s tacit knowledge.

The really important aspect of tacit learning, as any apprentice will tell you, is that it’s almost a process of osmosis. You gain more insight from simply being around someone, and sharing experiences with them, than you would do by explicit instruction. There’s nothing new in this revelation: it was, after all, Confucius who said “I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand”. Tacit knowledge is gained most frequently through ‘action learning’, working with others on problems, acting and then reflecting on those actions. That Polyani’s theories took hold at precisely the time that ‘knowledge management’ was gaining momentum must have been something of a mixed blessing for learning officers. There’s a limit to the amount of ‘managing’ of tacit knowledge that can be done.

The wisest course of action is to create the right learning environment, culture and context, which brings people together to learn from each other. The old joke that ‘collaboration is an unnatural act between non-consenting adults’ may have had its roots in corporations trying to break down silo mentalities. But if ‘open’ tells us anything, it points to a realisation that we have to understand how people learn when they have a choice (in what to learn, and who to learn with) and bring that into the places where they are required to learn.